‘Street Photography to Surrealism’ at The Frick: How an Art Form Expanded Its Focus

Many artists have done self-portraits in mirrors, but Ilse Bing added a dimension in her doubly mirrored ‘Self-Portrait with Leica’ from 1931. (Photo, collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg)

Tucked away near the end of Reynolds Street in Point Breeze, the art museum at The Frick Pittsburgh is one of the city’s semi-hidden gems. Admission is free. It is a friendly-sized museum: not large, but plenty big enough for a rewarding visit. And though the Frick has a concentration on older, representational art, it does a fine job of bringing art history—as well as history, period—to life. Especially in the special exhibitions, which just about any type of art fan can enjoy.

The current show (through May 5) makes the point. Sporting a long title—Street Photography to Surrealism: The Golden Age of Photography in France, 1900-1945—it includes photos by a cavalcade of big names, from Man Ray and Dora Maar to Henri Cartier-Bresson. The early street photographer Eugène Atget gets ample wall space, too.

Styles and subjects span a wide range. Silky nudes and portraits of glamorous art-world figures mingle with grotesque glimpses of the seamy Paris underworld in the 1930s. There are dramatic crowd scenes, and eerie compositions that turn reality dreamlike.

What you see here reflects a convergence of forces. Around 1900, the start of the era covered, photography was coming into full flower as an art form. Technical advances enabled further growth. (In the photo above, Ilse Bing uses a Leica, the first high-quality, super-portable 35 mm camera.) And during the early 1900s, Paris was the center of the art world, generating new movements and drawing foreign talent: Bing from Germany, Americans, Hungarians, and more.

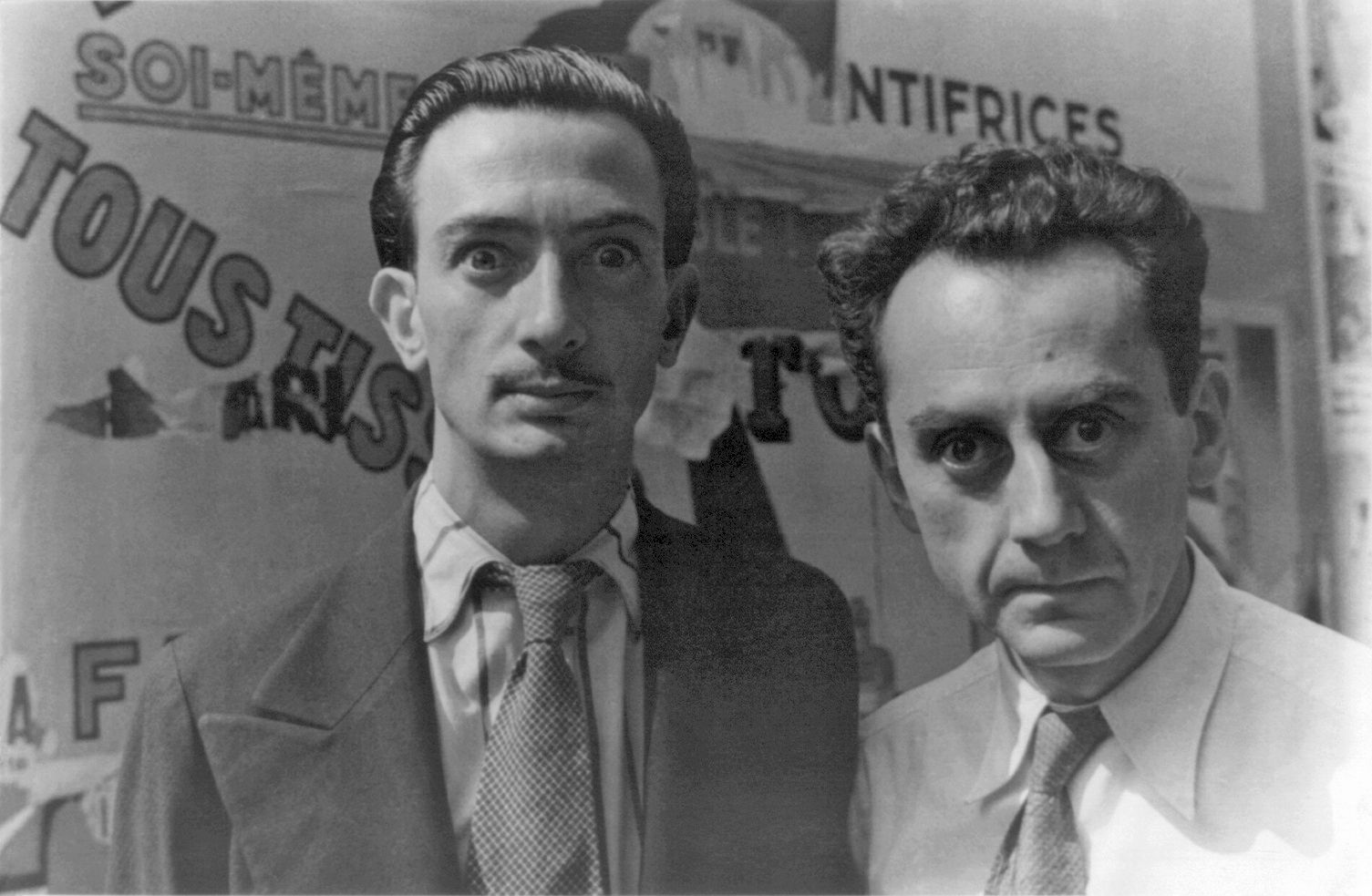

Not included in The Frick’s show, this snapshot captures two of the many foreign-born artists who frequented Paris between the World Wars. The shorter, intense guy on the right is American expat Man Ray. On the left, his fellow surrealist Salvador Dali. (Photo by Carl Van Vechten, 1934)

The result was lots of creative people exploring everything that could be done with a camera. Street Photography to Surrealism is a generous sampling of their work, 101 photos by 16 artists. The pictures trace the development of this not-so-dark art, and they may evoke feelings from disturbance to delight.

Unique touches by Frick Art Museum staff and others add to the experience. More about that shortly, after a look inside.

Bent Reality, Real Reality, the Art of a Deal

Numerous pictures display the use of weird props, poses, and/or processing tricks to make surreal or sorta-surreal images. Examples are strangely altered nudes from various artists, Pál Funk Angelo’s “Street of the Drunks” (a street scene that’s wavy, as in Whoa, better hold on to a lamppost), and several pictures by Man Ray, including an oft-shown self-portrait.

Visitors to such a diverse show will find their own favorites. My tastes are eclectic, but I particularly like straight-up, non-doctored photos, so let me highlight a few.

Foremost is an entire wall’s worth of photos by Henri Cartier-Bresson, one of the greatest to wield a lens with artistic intent. Few of his pictures were posed. Mostly, he took on-the-spot candids of people in public places—just shooting when the scene and the moment struck him, and refusing to crop the photos for enhanced composition afterward.

Yet his pictures have the power of inevitability. As if the hand of destiny, or the hand of a master painter, had arranged every face, form, and detail to be exactly the way it had to be, at the instant the shutter opened.

One picture was taken when the Catholic Church’s Cardinal Pacelli—later, Pope Pius XII—visited Paris. A crowd besieges him. In their midst is a young man passionately kissing the Cardinal’s ring, while a woman (perhaps the man’s wife) beams in fervent approval. Depending on how you see it, the picture conveys either the profound majesty of sacred love, or the madness of blind faith.

Did I say that Cartier-Bresson was good?

Photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue had an eye that caught a changing world on the fly. This foxy lady of 1911—decked in dead foxes down to the ankles—rocks the over-wrapped, woman-as-parade-float fashion that will soon become as obsolete as the horse-drawn carriage receding in the distance. (Photo © Ministry of Culture—France / AAJHL)

Of Ilse Bing’s photos, you may enjoy a sneaky-good one titled “Fortune Teller’s Booth, Street Fair, Paris.” It shows two exotically turbaned figures at their booth, and Bing has caught them out of character: one smoking a ciggie, the other appearing to make entries in a ledger book. The picture is not a crisp close-up; it’s a somewhat grainy longer shot, but it actually works better as such. You get a sense of spying through the haze on people who have dropped their masks, even while still in costume.

The show has scads of compelling photos by the Hungarian Brassaï (born Gyula Halász). Brassaï was fascinated by the Paris demimonde of brothels and streetwalkers, dance halls and thugs. He photographed the commoners of this world with sensitivity, rendering the hard ironies of their lives and, in some cases, the human spirit shining through.

One hard-irony picture that has stayed with me, uncomfortably, is a brothel scene. Three utterly naked young women are greeting, if that’s the word, a man fully dressed in tie and overcoat. The women are neither gorgeous nor ugly. They’re regular gals, standing with hands on hip in here-we-are mode. The man looks neither lusty nor thoughtful: not at all like the mythic hero contemplating three goddesses in the old “Judgment of Paris” paintings. He seems freshly in from outdoors and has the look that people had when breezing into stores back in the days before price-checking and comparison shopping were done on the web.

To me, the scene is more chilling than Brassaï’s photos of tough dames and gangsters. Forget about beauty, truth, and terror; this is a transaction. The art of the deal laid bare.

Personal Touches to Bring It Home

Street Photography to Surrealism was organized by the Ann Arbor-based company art2art Circulating Exhibitions, which serves small to medium-sized museums. The show has traveled to prestigious venues including the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, where it was customized by mixing the photos with paintings in the Barnes collection.

At the Frick Art Museum, the exhibit is more than customized. It has been personalized. Sarah J. Hall, director of curatorial affairs, explained how in an interview.

“The photography community in Pittsburgh has been amazingly supportive” of The Frick’s vintage photo shows, she said. Professors and instructors “bring their students here. They teach from the exhibitions.” A few years ago, Hall went on, this triggered an idea. Why not ask experienced photographers to share their insights with the public by writing “guest labels” for pictures they like best?

Hall first tried the idea with a 2015 show, Impressionist to Modernist. Now she’s brought it back in expanded form. Nineteen pictures in Street Photography to Surrealism have guest labels, each by a different Pittsburgh-based photo artist. The labels range from terse, witty comments to mini-essays that tell a story or delve into the method behind a photo. They’re instructive and fun.

For an intimate still life, “Mondrian’s Pipe and Glasses,” Sue Abramson points out how the photographer—André Kertész—arranged and shot the painter’s personal items to create striking geometric patterns. (Which is fitting, since Mondrian painted in a geometric style.) Abramson also says she has used the photo as a teaching tool—for an assignment that asked students to make self-portraits by taking pictures of their personal possessions.

Elsewhere, Ross Mantle’s guest label explains why a simple street photo by Dora Maar is so darned captivating: Among the people and objects there are “multiple unresolved gazes” that draw you into a bizarre “circle of looking.” And guest labelist Jamie Gruzska does a rambling riff on a spooky street photo, Lisette Model’s “Young Man Asleep, Paris.”

Gruzska poses a question: Why have sleeping persons always been popular subjects? Then, in the course of speculation, he writes, “Maybe titillation is the reason—could the subject be dead? We are left to wonder. How appropriate, since photography is always the dead returning.”

All are dead now: every photographer represented in the exhibit and most likely everyone in their pictures. 1900-1945 was long ago. But, as mentioned, the show at the Frick Art Museum does a fine job of bringing them to life.

While Claude Monet painted water lilies, Eugène Atget photographed them. Different ones, of course—these ‘Nymphaeas, Versailles’ lived far from Monet’s pond, around 1910, and Atget caught their nature: borne by water, fired by the sun. (Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg)

Closing Credits and Visitor Info

Street Photography to Surrealism: The Golden Age of Photography in France 1900-1945 was compiled by art2art Circulating Exhibitions from the collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg. The show is designed and mounted at the Frick Art Museum by Sarah J. Hall, with assistance from her staff and many others.

The exhibit runs through May 5. It’s free but online reservations are suggested for popular times. For visiting hours and further information on attractions at The Frick Pittsburgh, see the website or call 412-371-0600. 7227 Reynolds St., Point Breeze.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer, covers visual arts and theater for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter