Frida Kahlo in Photos: Twinned Shows at The Frick Pittsburgh Reveal an Artist’s Life

Although the Frida Kahlo exhibitions at The Frick are photography shows, this portrait on a New York rooftop may remind you of some of her painted self-portraits. (Photo 1946 by Nickolas Muray. Image © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives)

There was a time, during the 1930s, when Frida Kahlo was known as the wife of a famous artist. The tables have turned since then. Diego Rivera’s paintings are still admired, but Kahlo has become a legend—a subject of fascination both for her art and for her adventurous, often difficult life. The Frick Pittsburgh now offers a rare inside look at the latter with a twinned pair of special exhibitions, each showing photographs of Kahlo and her circle. Frida Kahlo—An Intimate Portrait: The Photographic Albums runs through May 30, and Frida Kahlo: Through the Lens of Nickolas Muray is up through May 9.

An Intimate Portrait consists of photos from the artist’s personal albums. They were provided by Vicente Wolf, a New York interior designer who had purchased the Kahlo albums for his collection. The show at The Frick, mounted and with text panels by the museum’s staff, marks the first time these pictures have been exhibited in the form you’ll see. All photos in Through the Lens of Nickolas Muray are by Muray, a professional photographer who was a longtime friend and sometimes lover of Kahlo. This is a traveling exhibition, which is why it must leave a bit earlier.

Frida Kahlo—born in 1907, in a town that’s now part of Mexico City—actually grew up immersed in photography. Her father was an architectural photographer, documenting the city’s history and growth, and she’d often help with work in his home studio. But Frida also grew up amid turmoil and pain that would shape her adult life. The long-running Mexican Revolution of 1910-20 split the country into various conservative and reform factions. Young Frida identified with the populist reformers. Politically, she became a lifelong communist. Aesthetically, she wove traditional folk-art motifs into her art and personal style.

Meanwhile illness and injury had set in. Polio in childhood left Kahlo with one leg shorter than the other, and though she tried not to let this slow her down, the physical mis-alignment aggravated further problems to come. As a teenager she had the bad luck to catch a bus that collided with a trolley. The accident put her in a body cast for months. During this time she began to paint in earnest, while getting to know a companion she’d have for the rest of her life: chronic pain. Spinal injuries from the accident never healed properly. Multiple surgeries over the years, including one to brace her spine with a metal rod, didn’t help. Her 1944 self-portrait “The Broken Column” vividly depicts the woman she felt she had become: strong and beautiful, but violated and tortured.

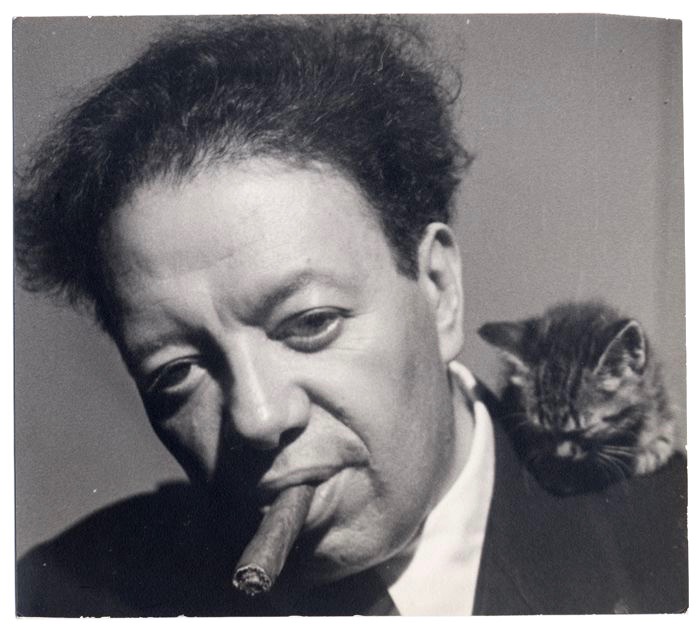

Diego Rivera, captured here in a portrait oozing with symbolism, cast both light and shadows across Kahlo’s life. (Photo circa 1929 by Tina Modotti, from The Vicente Wolf Collection)

The Intimate Portrait show “is almost like an illustrated biography” said Melanie Groves, manager of exhibitions and registrar at The Frick. Groves directed the design of the show, grouping the photos into five sections that highlight major aspects of Kahlo’s life. One section traces the course of her marriage at age 22 to the older, already prominent painter Rivera. This union, interrupted midstream by a divorce and remarriage, had far-reaching consequences. Rivera was a serial womanizer who at one point devastated his wife by having an affair with her younger sister. Kahlo reciprocated by engaging in her own affairs with other men and, occasionally, women. Rivera was commissioned to paint murals in cities throughout the United States; Kahlo traveled with him and, in the process, started gaining recognition for her own paintings.

While her art certainly is striking, Kahlo stands among the few artists who’ve also attracted a massive fan base as a person. Perhaps one reason was her response to ongoing challenges, both physical and emotional. As Groves put it in a phone interview, “She experienced the darkest of the dark. And yet she turned intentionally to enjoy life and love.” The exhibitions manager noted that many photos at The Frick bring out this quality, conveying, for instance, Kahlo’s “impish sense of humor.”

Another factor in Frida’s popularity is that she made herself an integral part of her art, and vice versa. Along with painting numerous self-portraits (a tendency shared with her father, Guillermo, who was fond of making photographic self-portraits), she liked to dress and live artistically. The Intimate Portrait show explores this theme in a section titled “Frida and Fashion—Defining Herself.” Groves would invite us to notice that she didn’t define herself in only one way: “She understood and embodied that a person can be many things at once. You’ll see her posed in her dad’s suit, playing the masculine part, and then later that same day she’s in a feminine dress and heels. From minute to minute, we can be something different. As Frida was.”

Groves further pointed out that Kahlo’s art was very much about “connecting with people. Many of her self-portraits were gifts to friends … She used photographs almost as trading cards; she used them as calling cards.” Again and again, the message was Here I am. Please think of me, and think of yourself with me. Does that sense of connection come across at The Frick? “I believe it does,” Groves said. “And I hope people have fun when they come in!”

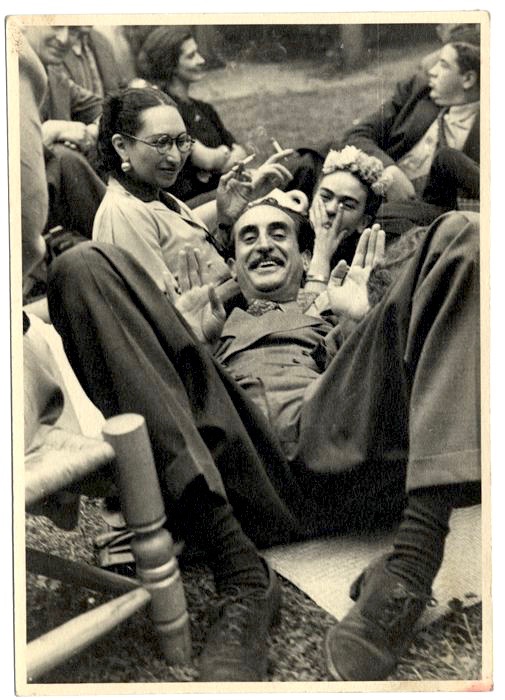

The Frick Pittsburgh’s Kahlo photos range from high-art compositions to snapshots like this. The illustrious gentleman in suede shoes is painter and film director Adolfo Best Maugard. Arts patron Malú Cabrera Block is the lady in specs and that’s Frida giving a hand signal with nose in midst. (Photo undated and unattributed, from The Vicente Wolf Collection)

Closing Notes and Visitor Info

Frida Kahlo died in 1954, at the age of 47, when her body could no longer keep going. To say that her legacy lives on is an understatement. She is now regarded as a feminist icon, an LGBTQ icon, a social-justice icon, and a Mexican national treasure—not to mention an artist whose work continues to fascinate millions.

The Kahlo photo exhibitions at The Frick Pittsburgh require timed entry tickets in advance. An admission fee is charged. Entry to the Art Museum’s permanent collection and the adjacent Car and Carriage Museum is free. Open Tuesdays through Sundays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. at 7227 Reynolds St., Point Breeze.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer, covers visual arts for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter