Art Speaks in Many Languages at the Carnegie International

Big show, big picture. Visitors to the Carnegie International are greeted by Mimi Cherono Ng’ok’s super-sized piece, which even has a big title: ‘Here in the weary world somewhere between time and space we shall be free …’ (photo courtesy of the artist)

If you are wondering whether to see the 57th Carnegie International, the answer is yes. It has always been yes. The International, presented every few years by Carnegie Museum of Art, is a rare chance to see a cross-section of work by contemporary artists from around the world. The only imaginable reason to miss one would be not caring for modern art.

… But wait, there are videos. They include three hours’ worth of hilarious shorts by Alex Da Corte, plus a documentary about factory workers, plus the first-ever ventures into video by novelist Han Kang, acclaimed author of The Vegetarian, and more. Screen content alone equals a small film festival.

The current International (through March 25) is a big show, so big that the real question is how best to enjoy it. Two tips may help.

Advice for Max Enjoyment

One, be open to anything. Today’s art world is eclectic in the extreme. No style, genre, or -ism predominates. The International reflects this, and what it means for visitors is that different kinds of art invite you to get into them in different ways.

Abstract or semi-abstract art, like Thaddeus Mosley’s sculpture, invites a sheer sensual experience—feeling one’s way in through the eyeballs, as it were—while conceptual art tickles the mind. Some pieces tell stories, though not always in “Once upon a time” form, and some stuff comes across as just plain beautiful or weird. All told, the International is the artistic equivalent of a full-body gym. It offers everything from free weights to aerobics to meditative yoga.

And thus the second tip: go more than once. “The exhibition gets richer with subsequent visits,” Associate Curator Liz Park says. “There’s a lot to explore. A lot of layers to explore.” Multiple shorter visits also help avoid shopping-mall burnout, the weariness that’s a mix of tired feet and too many choices. Pittsburghers can buy a Carnegie Museums membership, which makes each trip to any museum in the local Carnegie family free for a year thereafter. Out-of-town visitors would do well to invest in two partial days rather than one marathon.

The Pittsburgh Connections

Decisions, decisions: Members of the art collective Postcommodity visited old Pittsburgh-area industrial sites to find materials for their entry in the International. (photo: Carnegie Museum of Art)

Putting together the 57th International was a marathon task. Curator Ingrid Schaffner and her crew spent three years assembling the show, striving to make it both globally diverse and uniquely a Pittsburgh event. Along with including three artists based here, they brought in non-resident artists for pre-show tours of the city and the museum. All were encouraged to create work that somehow fit the scene, if they so wished, and many did.

This has led to some interesting adventures in site specificity, as we’ll see, for now comes the part of the story that is uniquely reviewer-centric. Come along while I show you my favorites.

Solid Wood from the Tree Wizard

Some Thaddeus Mosley sculptures look like giant chess pieces with minds of their own, and they might be. (photo: Bryan Conley)

Making a strong stand is a cavalcade of work by Thaddeus Mosley, the longtime dean of Pittsburgh sculptors. Mosley hand-hews abstract shapes from logs and branches, producing big wood sculptures that span the range of adjectives—from brutally chunky, to soaring and willowy, to playfully whimsical. The International has 14 of these in the entrance lobby. The arrangement creates a multi-barreled effect, as each piece in itself is striking, and the setup makes them dance together. It’s like viewing an art forest. Or meeting a squadron of fantastic tree-creatures. (See a video of Mosley in his studio.)

Art from Scrap: Ruins of the West

The Hall of Sculpture is a dramatic space, a vast marble-floored room ringed by a balcony from where replicas of ancient heroic statues look down at us mere mortals. Only an epic piece belongs here. Something like “From Smoke and Tangled Waters, We Carried Fire Home.”

Postcommodity’s ‘From Smoke and Tangled Waters, We Carried Fire Home.’ (photo: Bryan Conley)

The artists are indigenous Americans in a collective called Postcommodity. They say the sprawling piece is inspired by Navajo sand painting, except they’ve drawn their materials from the leavings of Euro-American industry. The patterns covering the floor are made of coal and crushed white glass. Piles of rusted scrap steel are placed strategically throughout.

The symbolism needs no explaining. For me, it called to mind a line from T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land: “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.” But the Postcommodity artists have done more than make a haunting statement. Let me introduce you to a friend.

With me on a visit to the International was Chuck Barr, a man known for wearing two hats in Pittsburgh’s indie culture: outsider artist and free-jazz musician. Chuck’s approach to art is musical—he can sense the rhythms and melodies in stationary objects—and wow, did he get into the Postcommodity piece. We walked all around it at floor level, stopping to dig the patterns formed by various stacks of scrap metal. We leaned in close to feel (with our eyes, not hands!) the chunky textures of the black-coal areas, and how they harmonize with the fine-grained glistening of the white areas.

Then we went upstairs to the balcony for an eagle-eye overview. “This is inspiring me, man,” Chuck whispered. “It makes me think about new structures and ideas for my art.” And that’s how art lives on: the torch is passed. From smoke and tangled waters, we carry fire home.

Cottage-Industry Videos

Alex Da Corte’s “Rubber Pencil Devil” is a crowd favorite, not only mine, and deservedly so. It’s an installation that fills a small gallery. The exterior of the piece is a skeletal framework of a cutesy cottage, all lighted up in neon. This gives the gallery space a fairy-tale glow, but the main treat lurks inside grandma’s house. Instead of the Big Bad Wolf you find a large video screen. It plays a continuous loop of short videos which are exquisitely made and exquisitely funny.

Youngsters please note: Alex Da Corte makes bold art but when the making gets messy he wears safety gear. (photo: Jannick Boerlum)

Most music videos look crudely overdone by comparison. Da Corte and his creative team do not indulge in rapid cutting between busy-busy scenes to make it look as if something’s happening. They use special effects sparingly. The videos are little gems, most of them played out in pantomime by actors (including the artist himself) who know how to move, on studio sets designed with artful simplicity.

And the comedy in “Rubber Pencil Devil” just keeps coming. Subjects include Satan’s weather report, a Mister Rogers tribute, and a pair of drag divas lip-synching the doowop ballad “My Heart Cries”—which they do with a fine understatement that’s much funnier than taking it over the top.

In another pitch-perfect video, Da Corte enters neatly dressed and carrying an umbrella. Walk-dancing gracefully, he launches a lip synch of Dolly Parton’s inspirational anthem “(I Can See the) Light of a Clear Blue Morning.” The song rises and swells. Wielding the umbrella like a conductor’s wand, the actor rises and swells with it, pressing ahead even as studio-effect rain rolls in.

The video is a hoot and at the same time magnificent. It evokes classic movie scenes such as Gene Kelly’s “Singin’ in the Rain,” and Vernel Bagneris’ powerful “Pennies from Heaven” in the Steve Martin film of that title. I’m guessing Da Corte got the idea from those scenes, because again, that’s how art lives on.

Shows Within the Show: a Tunnel of Colors, Empires on Parade

Several artists at the International are given entire galleries or areas that they’ve filled with mini-exhibits. These shows within the show contribute greatly to visitor experience. You can abide for a while in them, absorbing the distinctive vibes, messages, or whatever that each conveys.

Beverley Semmes’ FRP Arcade turns a tunnel-like corridor of the museum into a tunnel of intrigue. FRP stands for Feminist Responsibility Project, conceived by Semmes for altering photos of naked or nearly naked women from so-called adult magazines. She enlarges the images and overpaints them to cover the women’s bodies, often leaving only certain features exposed: perhaps a face, or a gesturing arm. Five such paintings are in the Arcade, but the tunnel houses much more of Semmes’ work—all in vivid colors.

Electric lime-green fabric draperies hang on one wall. There are 21 small, colorful paintings, from abstracts to three renditions of a cardinal (the bird, not the religious officer), and if I were a plutocrat swimming in oil money I’d buy the lot. Seldom have I felt so color-infused. All that plus feminist critique: who could ask for more?

In Koyo Kuouh’s ‘Dig Where You Stand’ exhibit, an African headpiece is mixed with items like the silhouette on the far right: Augustin Edouart’s 1842 ‘Portrait of the Honorable John W. Blessing.’ The gentleman wears a high hat and holds, behind his back, a whip. (photo: Brian Conley)

And yet more awaits. Koyo Kuouh’s Dig Where You Stand is a commentary on colonialism, or, as the artist puts it, coloniality. For this show-within-the-show, she combed through the museum’s permanent collections (including items in storage) to choose works representing both indigenous peoples and European colonizers. Kuouh, an exhibit-maker and arts producer from Cameroon, chose well. The pieces are good art and the mixture makes one think.

One standout is a Cecil Beaton photo of Queen Elizabeth II, the current monarch, at her coronation in 1953, when she was 27. Looking plucky but vaguely uncomfortable, the young woman is decked in an outrageous array of imperial bling. In her hands she holds the fantastically bejeweled orb and scepter of empire. On her noggin, Elizabeth balances a royal crown that’s not nearly as big as many big hats worn throughout history by various big shots, but this is England. A chapeau the size of a layer cake clearly says who’s on top, and it is exactly not too much.

Art from Words

Tom Wolfe’s 1975 book ‘The Painted Word’ criticized modern art for being too theory-driven. Artist Mel Bochner responds with painted sentences. Just out of view: ‘LOOK WHO’S TALKING.’ (photo by Brian Conley, courtesy of the artist and Peter Freeman Inc.)

Mel Bochner, a native Pittsburgher and Carnegie Mellon graduate, was a pivotal early figure in conceptual art in the 1960s. For the International he made a group of his short sentences painted on canvas: “MISTAKES WERE MADE” seems to be popular. The paintings are new, but text-based art is not.

Decades ago, Robert Indiana’s “LOVE” was reproduced on a postage stamp. Jenny Holzer is a leading text artist; her “PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT” has been displayed in giant-sized light-up letters on buildings, and printed on packets of prophylactics. Media prankster Kembrew McLeod obtained a registered U.S. trademark for the phrase “Freedom of Expression,” then put up a Freedom of Expression® website and wrote the book Freedom of Expression®.

So there’s a sizable history of the form, and the International adds a couple of new twists. Around the exterior of the historic Carnegie Museum building, under the eaves, the last names of great men of art and science are carved in stone: Rembrandt, Mozart, Michelangelo, Galileo, and many more. They’re all famous white men. Now Bahamas-born artist Tavares Strachan has added some color to the frieze.

As part of his ongoing “Encyclopedia of Invisibility” project, Strachan overlaid the names of 50 less-recognized achievers—mostly persons of color—in bright neon-lighted script. They range from Norgay (Tenzing Norgay, the Sherpa mountaineer who, with Edmund Hillary, made the first ascent of Mt. Everest) to Lamarr (actress and inventor Hedy Lamarr). Viewed on a dim day or at night, the names look sharp, and they may inspire you to look up who did what.

Detail of Tavares Strachan’s ‘The Encyclopedia of Invisibility.’ Sombath Somphone, honored for his work in rural and agricultural development in Laos, was for unknown reasons detained by Laotian police in 2012 and hasn’t been seen since.

Indoors, the Forum Gallery houses a very popular exhibit-in-action by Pittsburgh conceptual artist Lenka Clayton and her colleague Jon Rubin. The exhibit is called “Fruit and Other Things,” which was the title of one of 10,632 works of art rejected from the International between 1896 and 1931, when the show took submissions at large. It’s too late for a standard salon des refusés, since the paintings and such are long dispersed. But the museum kept records of the 10,632 titles, so Clayton and Rubin conspired to make art from those.

Thus “A Sleeping Mortal” awakes—perhaps to “Daybreak in Cincinnati,” or, more metaphysically, to a “Day of Correction.” The gallery is now a handwork factory, with rotating pairs of artisans lettering the titles one-by-one in black paint on white placards. Some are inscrutable and vaguely disturbing: “Boy Grapes.” Finished titles line the gallery walls, while a human line forms in the center: if you wait your turn, you can take a title home with you.

And to carry home a Mel Bochner, visit the gift shop. They’ve got nice black t-shirts printed with his “DO I HAVE TO DRAW YOU A PICTURE?”

A Ghostly Presence, a Comic Strip, a Final Tip

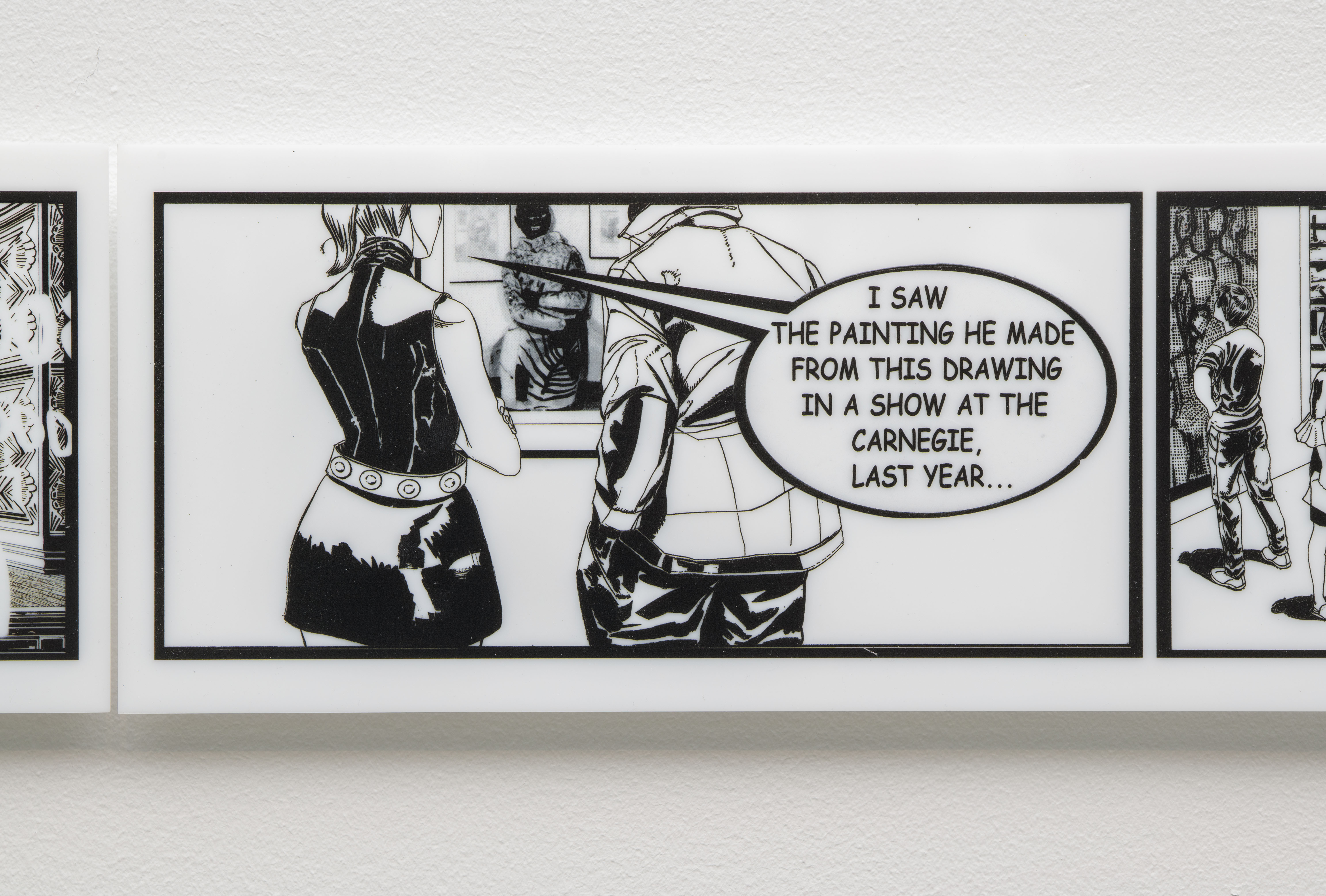

Kerry James Marshall here, gracing the walls with frames from his ‘Rythm Mastr.’ This one is self-referential and the painting is in the permanent collection. (Image courtesy of the artist and not for repro.)

Other highlights? Be sure to commune with Huma Bhabha’s “Memories of the Future.” This gigantic, eerie, human (or humanoid?) figure, sculpted from various materials, manages to be sensational and spookily subtle all at once. Fans of Kerry James Marshall—my hand is waving eagerly—may be disappointed that the International doesn’t feature the spellbinding impact of his huge paintings of urban life. The consolation prize is cool, though: a 70-foot-long sampling of Marshall’s comic strip “Rythm Mastr,” which the Chicago-based artist premiered in Pittsburgh in 1999.

One final tip. When you visit the 57th International, pick up a fold-out guide to the show at the front desk. Some fine works are in nooks and crannies where they’re hard to find. Don’t miss what you might like the most.

Closing Credits and Visitor Info

The 57th Carnegie International is curated by Ingrid Schaffner, with her team members Liz Park and Ashley McNelis. Through March 25 at Carnegie Museum of Art, 4400 Forbes Ave., Oakland. Numerous special events are scheduled in conjunction with the International. For a listing of these, as well as links to museum hours and other information, visit the International site on the web.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer, covers visual arts and theater for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter