‘What Do You See?’: The Fine Collection at CMOA

As a conceptual project, artist John Baldessari once burned his early paintings and had the ashes baked into cookies. But then he made artworks like this, now part of the special show at Carnegie Museum of Art. Title of the picture above: ‘Nose & Ears, Etc.: The Gemini Series: Two Profiles, One with Nose and Turban (B&W); One with Ear (Color) and Hat.’ Image © John Baldessari and his estate, courtesy Sprüth Magers; photo: Sean Eaton.

If you want to commune with visual art in relative solitude—traveling deep into worlds of images, without crowds milling around—try a weekday morning visit to Carnegie Museum of Art. On a recent Friday morning, the only customers in the museum’s shiny, spacious Heinz Galleries were two groups of students on field trips. And nobody was making noise or even saying much. Under the sotto voce guidance of a docent, a cluster of high-school teens stood before an immense, swirly, abstract canvas titled “Noah’s Third Day.” Lots to occupy the eye. Hard to say what to make of it.

Meanwhile, off in a corner, about two dozen middle-schoolers sat on the floor near a large photograph. Thomas Demand’s “Fenster (Window)” is a spare and spooky photo of a wide window, screened by vertical blinds, with backlight glowing through. The docent here, a young woman, prodded the students to react. “What do you see?” she asked. “Does it remind you of anything?”

I didn’t eavesdrop close enough to hear the murmured replies. I did, however, notice a few kids fixated on gazing at the photograph. Gazing raptly, as if wrapped in its spell. That’s the spirit. And the current show in the Heinz Galleries, The Milton and Sheila Fine Collection (through March 17, 2024), offers an excellent chance for anyone to catch the spirit of contemporary art.

How a Silent Language Speaks

Of all the art forms, the static visual arts—painting, sculpture, still photography, etc.—can be the most challenging to relate to. There’s no action unfolding to grab your attention, no music to rouse your rhythmic instincts. Just stuff to look at. I have watched people in art museums staring uneasily at masterpieces and glancing sideways at their friends for clues to what’s what. The scene is reminiscent of the famous cartoon of two Zen monks, a young one and an old one, sitting side by side in meditation. The young guy wears a puzzled expression. The old monk scowls and says “Nothing happens next. This is it.”

The good news is that with visual art, plenty can happen, once a person gets into the practice of just looking. It’s been said a picture is worth a thousand words, but the truth is more radical.

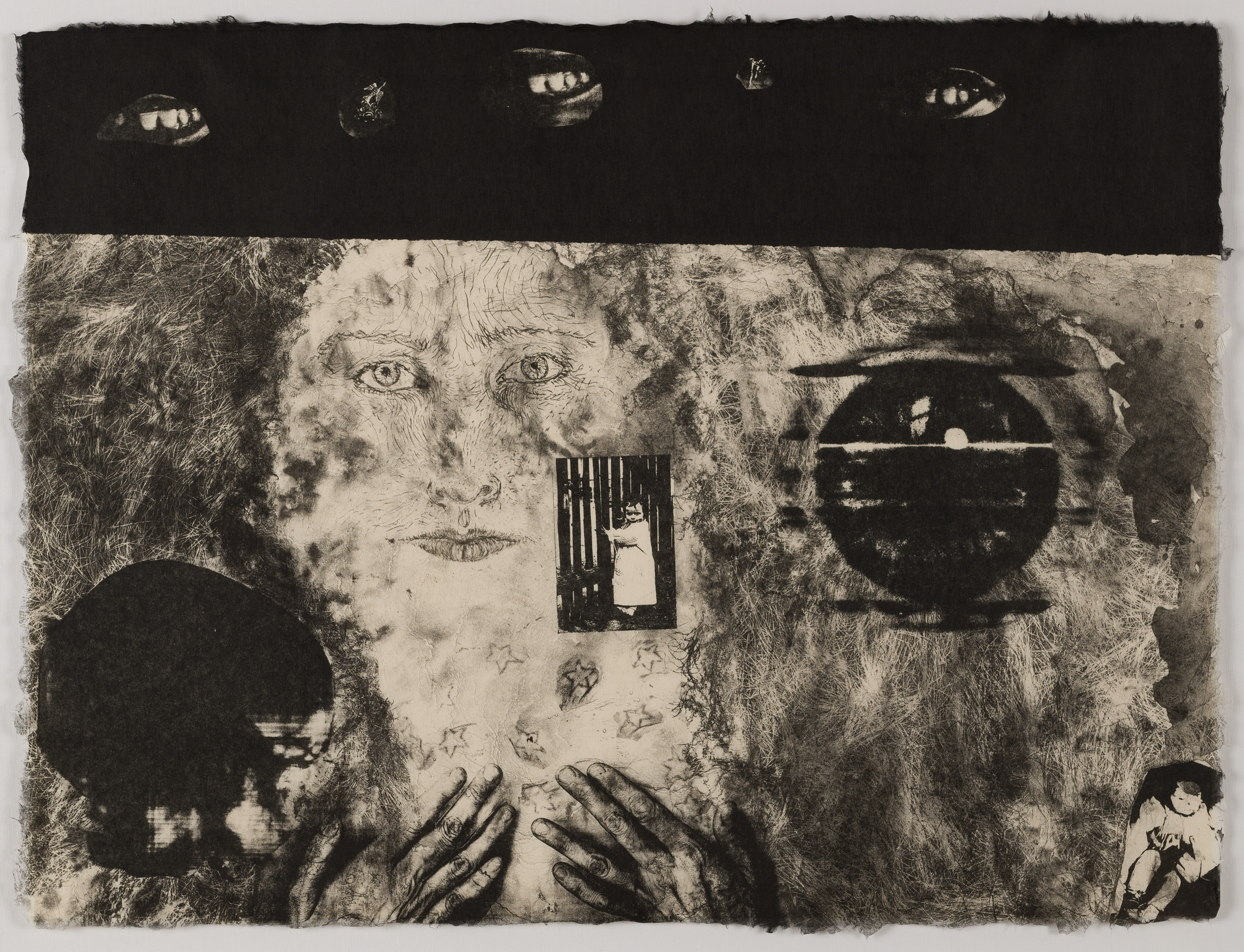

Here’s looking at you: one of several pieces in Kiki Smith’s ‘Banshee Pearls’ series. Image © Kiki Smith and Universal Limited Art Editions; photo: Bryan Conley.

A good picture by a good artist does things that words cannot. It can jar you into seeing outside the box. It may radiate, or evoke, swarms of ambiguous and yet somehow vital thoughts and feelings—but why spend words trying to capture what non-words do? Just take time to look.

The art in The Milton and Sheila Fine Collection adds up to a looker’s feast. A total of 95 pieces, which range from abstract to hyper-real, constitute a ‘round-the-world sampling of works created during the latter half of the 20th century and early 21st. Showcasing a diversity of artistic M.O.s, as exercised by artists across a spectrum from Sol LeWitt to Cindy Sherman to R. Crumb, the exhibition is like a mini-museum. And it has an intriguing backstory.

About the Fines

Born in Pittsburgh to immigrant parents of modest means, Milton “Milt” Fine (1926-2019) lived a life that embodied many dreams of the so-called greatest generation. After growing up in the Depression era and serving in World War II, he made his mark as an entrepreneur in the hotel industry, then segued to investing and philanthropy. Along the way, a fascination with art led him to start collecting. He married the former Sheila Reicher, who shared that passion, and a strong bond grew between the Fines and Carnegie Museum of Art. Experts from the museum had advised Milton on his collecting; he became a trustee of the museum and eventually chaired its board.

The Fines expanded their holdings by buying works from the Carnegie Internationals, the museum’s periodic exhibits of cutting-edge contemporary art. Further, the couple agreed that upon Milton’s death, a trove of the art they’d acquired would be donated to CMOA. This prodigious gift is now the basis of the Fine Collection show. After it closes, various artworks will gradually go on public view in places throughout the museum. But now is when to see them displayed en masse, to great effect.

Art Power

A zinger that’s worth viewing up close and in person is Mark Grotjahn’s ‘Untitled (Colored Butterfly White Background 6 Wings 594).’ Photo: Carnegie Museum of Art.

Within the Heinz Galleries—a corridor of big, airy spaces devoted to special one-time exhibitions—each room surrounds you with a kaleidoscopic view of what’s been done by artists of recent decades. Bold abstract paintings mingle with eerily enticing smaller pieces. Familiar faces and names leap out: e.g., a portrait of the artist Keith Haring, photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe in 1984, a few years before both men died in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. And the show is a fine occasion to get acquainted with the work of many who aren’t so publicly known, from Mark Bradford (the “Noah’s Third Day” artist) to the sculptor Judith Shea.

The rear Heinz Gallery for this show strikes me as one of the most spectacular museum spaces I’ve ever seen. On a platform in the center stand three sculpted human figures, each facing outward and commanding the room in its own distinct way: Shea’s sleekly powerful “ARTIST,” Anne Chu’s jaunty “Maranao Man,” and Matthew Monahan’s bizarre “Phantom Limb.” The walls around the figures bloom with an astounding parade of art in multifaceted forms. And what makes the room sing, along with the art itself, is how it’s arranged.

An astounding arrangement of art. At the center is ‘Phantom Limb’ by Matthew Monahan. Photo: Chris Uhren

“For anybody who’s not very familiar with contemporary art, the [entire] exhibition is great because there are so many different styles and such a range of approaches to see,” the museum’s Cynthia Stucki said when interviewed by phone. Stucki was part of the curatorial team designing the Fine Collection exhibit. One reason the show works well, she noted, is that the team refrained from trying to impose an overarching concept: “We didn’t organize it chronologically or in any art-historical manner.”

As a result, the exhibit isn’t over-intellectualized. You won’t be force-fed attempts to emphasize particular movements or -isms. Instead, according to Stucki, the artworks were placed mainly with an eye to how they would relate to each other, as in the grouping of the three sculpted figures. For visitors who might want to venture into art history, she advised stepping through the side door of the rear Heinz Gallery into the museum’s adjoining Hall of Sculpture. This ornate space is lined with ancient Greek and Roman statues—gods and goddesses, heroic warriors and athletes—which immerse you in a traditional way of depicting the human form. Then return to the Fine Collection to view the trio of contemporary sculptures again, and “You can see how three different artists take that tradition in different directions,” Stucki said.

Contrasts and strange resonances abound elsewhere in the show. Although photographs are placed throughout the Heinz Galleries, many are clustered in one area, where they vary tremendously in both subject matter and treatment. There are classic portraits along with “studio-created” scenes that bend the classical style, plus dynamic street photography, dream-like seascapes, and photos that border on the surreal. On the one hand, said Stucki, “It’s interesting to be able to make those comparisons”—while on the other hand, the absence of sameness invites you to really look at every image. And that was the curators’ intent with all of the art, Stucki noted: “I think it allows visitors to take each object for what it is.”

If there is a unifying theme to the show, it lies in how Milton and Sheila Fine collected art. They saw contemporary art as an ongoing adventure. It’s clear that their tastes were eclectic and their attitude open-minded. Put your head on similarly when you visit. You’ll be rewarded.

Everybody loves puppies, including probably Jeff Koons, who made the sculptural assembly ‘String of Puppies.’ Image © Jeff Koons; photo: Bryan Conley.

Closing Credits and Visitor Info

The Milton and Sheila Fine Collection exhibit at Carnegie Museum of Art is organized by Eric Crosby—the museum’s Henry J. Heinz II Director and Vice President, Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh—along with Tiffany Sims, the Margaret Powell Curatorial Fellow, and Cynthia Stucki, curatorial assistant for contemporary art and photography. Through March 17, 2024 at 4400 Forbes Ave., Oakland. Visit the show’s webpage for more information.

The museum is closed on Tuesdays, as well as on Christmas and New Year’s Day. Otherwise it’s wide open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and until 8 p.m. on Thursdays.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer, covers the visual arts and theater for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter