Note to Self: Joan Brown Exhibit at CMOA

Joan Brown, ‘Noel in the Kitchen,’ 1964. Oil on canvas; 60 x 108 in. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Bequest of Dale C. Crichton © Estate of Joan Brown. (Photograph: Katherine Du Tiel)

To compare the style and subjects of notable visual artists is, in most cases, an exercise for academic amusement. Visual artists typically become notable principally because their subjects––and the styles by which they are rendered––are their own; inimitable, unusual, or deeply personal. An exhibit of Joan Brown’s work has just opened at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Oakland. She, a proud daughter of the 1960s-90s San Francisco Bay Area who found early acceptance, even in NYC galleries, is much respected for her colorful, and sometimes textural, works revealing what she considered most personal to her: Joan Brown.

Seemingly, every significant visual artist of the past century has painted at least one widely acclaimed self-portrait. Van Gogh painted many. Picasso and Frida Kahlo, too. Albrecht Durer is often credited for making one’s self-image an acceptable subject others might appreciate. Joan Brown insists that that is so. The Carnegie’s exhibit, which follows a larger Joan Brown show first mounted at SFMOMA last November, is resplendent with forty of the artist’s self-portraits.

The daughter of an ambitious banker and a chronically depressed mother, Joan Brown discovered her ambitions when she attended the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute, but then the oldest art school in the west) and there adopted teacher Elmer Bischoff’s instructions to “paint what was most familiar to her.” Apparently, Brown loved holidays. The first piece in the Carnegie exhibit is a Thanksgiving turkey, a study of brown on green with barely sufficient form to identify the subject. The second work is one of her son, aptly named Noel, sitting under a Christmas tree, heavily tinseled, surrounded by Christmas images (or are they ornaments?) of Santa Claus, gingerbread men, and the like. Her child’s eyes are large, black orbs. Brown has painted the image with many layers of paint. Her brush strokes might be considered by some as “loose,” except that the many layers of paint under these strokes suggests the artist was perhaps more frustrated than loose. Following these early works, the Joan Brown exhibit then advances her self-portraits.

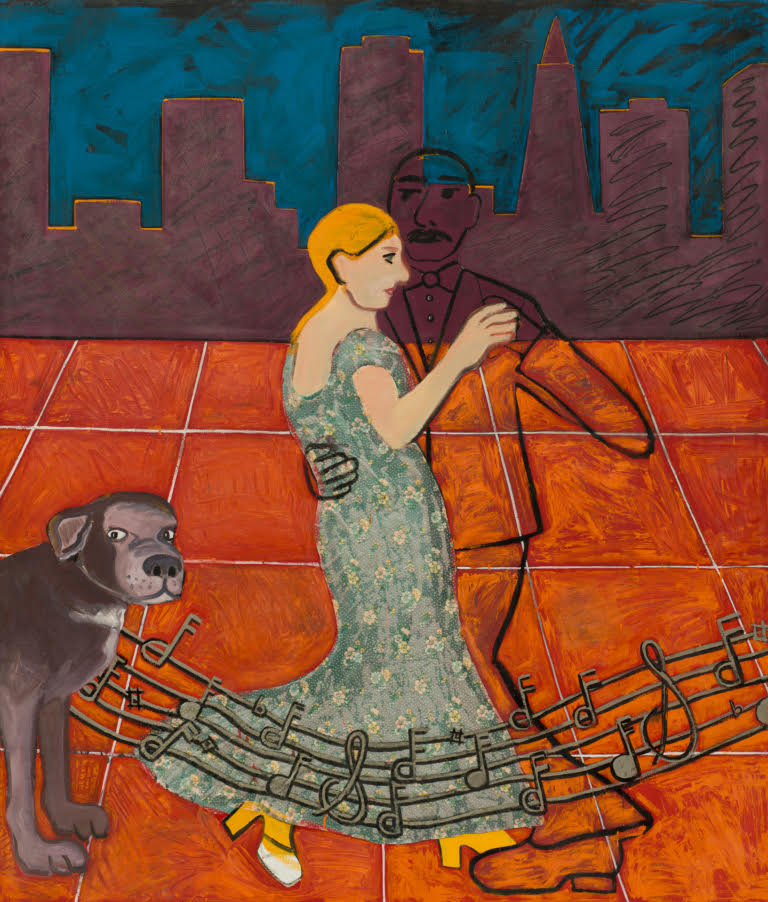

Joan Brown married four times. Her second husband (and father of Noel) was artist Manuel Neri, also a notable Bay Area artist. The exhibit includes a scene of their honeymoon, husband and wife posed at the Alhambra Mosque, costumed. Her third husband, Gordon Cook, the Chicago-born artist, loved to dance. Several large works depict them together on the ballroom floor. A cardboard sculpture of a trans-Atlantic steamship reveals many couples dancing on its deck during an ocean cruise. Happily, Brown worked in more than just oils. In fact, one interpretive statement explains how Brown discovered the wonders of hardware store paint that brought to her work bright colors (and a faster drying time) and changed her artistic expectations. Indeed, her later works are more brilliant and more detailed than her earliest and looser expressions.

Joan Brown, ‘The Dancers in a City #2,’ 1972. Enamel paint and fabric on canvas; 84 x 71 3/4 in. San Francisco Museum

of Modern Art, Gift of Alfred E. Heller © Estate of Joan Brown. (Photograph: Katherine Du Tiel)

To suggest that Joan Brown was self-absorbed may have some truth to it, but her self-images are not glamorous, not necessarily flattering and not always center stage. Large painting after large, the visitor begins to understand that, while Brown includes herself in almost every painting, her artistic exploration is not vain nor egotistical. Her work seems to be more sentimental, more a purposeful record of life events and places she has visited than studies of herself. Known for her love of swimming in San Francisco Bay at sundown, she painted a portrait of her swimming coach, Charlie Sava, but she included herself along with him. Other portraits in which she stands at a mantel or reclines in a chair feature paintings within paintings depicting events, like swimming from Alcatraz, that seem designed to memorialize that achievement. Her works are colorful, often flat, almost primitive in lacking depth or shadow, but they are joyous, compelling and curiously expressive.

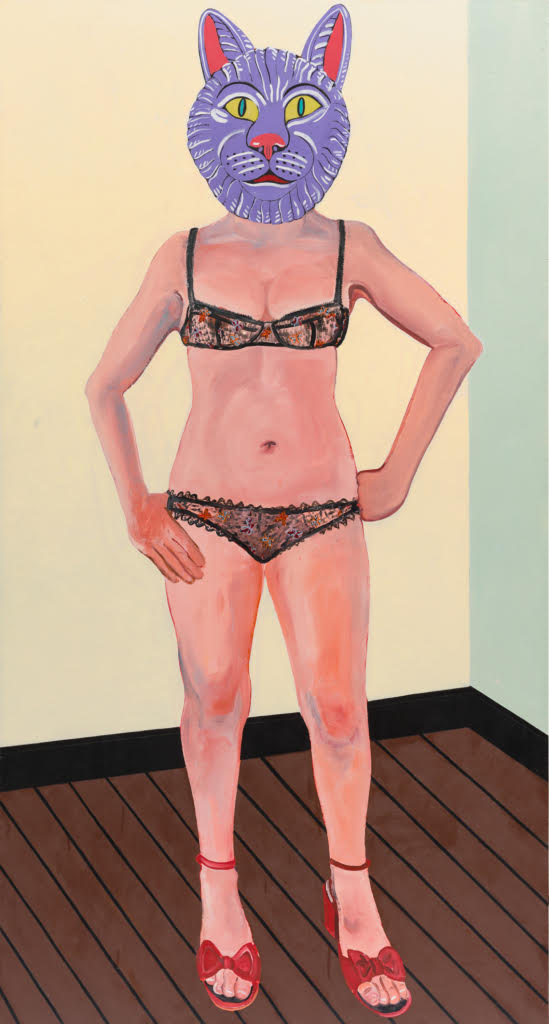

Most of her work includes a pet dog or cat. At times, she depicts herself wearing a cat mask. In later works, she includes animals in symbolic forms. Her later works reveal an affinity for Hinduism, a result of meeting yogic guru, Sathya Sai Baba, while visiting the Himalayas with her fourth husband, Mike Hebel, a cop turned lawyer (who was not an artist.) In 1990, while in Southern India installing a sculpted obelisk to honor her spiritual journey, she was killed when a floor collapsed in the building in which she was working. As ironic and disturbing as her death was, Joan Brown lived large and boldly.

Joan Brown, ‘Woman Wearing Mask,’ 1972. Oil enamel on Masonite; 90 1/8 x 48 in. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Audrey Taylor Strohl © Estate of Joan Brown. (Photograph: Katherine Du Tiel)

The Carnegie exhibit is wonderfully staged, her works openly spaced, its several expository statements informative and not just mundane “art speak.” Brown’s work is shown chronologically, although there are necessary gaps of time, so prodigious was the body of her work. Pittsburgh visitors will realize that the Carnegie’s offering is but a small share of what San Francisco featured recently. Yet, what is here to see is worth far more than an afternoon’s visit. The Joan Brown exhibit runs through September 24.

Prentiss Orr writes about theater and art for Entertainment Central. His latest book, The Surveyor and the Silversmith, is a history of white settlement, genocide, and land speculation in Western Pennsylvania.

Share on Social Media

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter