Out of the Shadows: Edward Hopper at Carnegie Museum

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

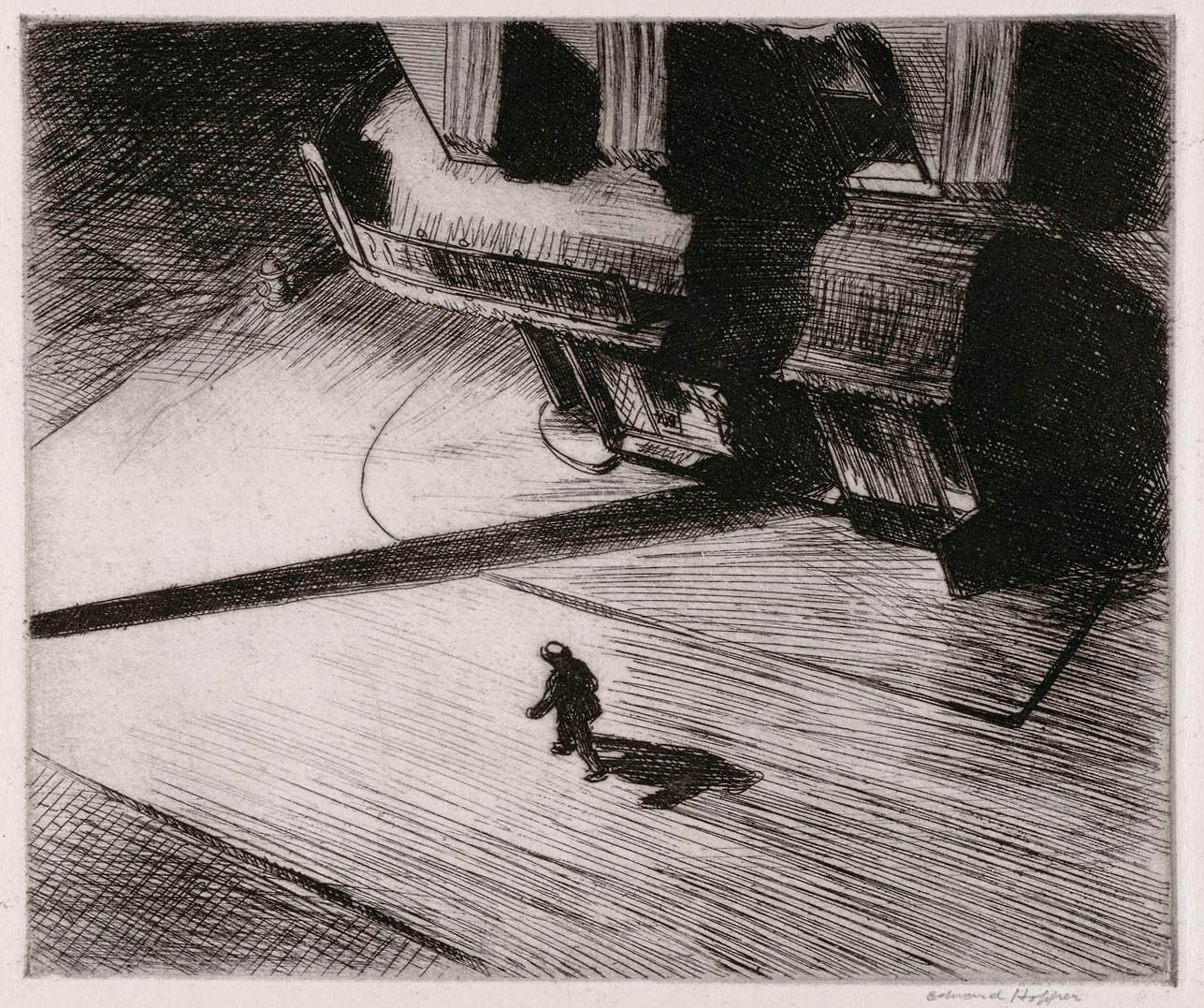

Hopper’s spooky 1921 etching “Night Shadows” is part of the special exhibit at Carnegie Museum. The show includes bright and sunny rural scenes, too, though it’s unsure if this man will find them.

Have you had a Hopper flashback lately? The other day I experienced one that lasted nearly an hour. It began while driving on a lonesome, looping rural road. The sunlight was slanting. The sky and air were as clear as a window frame with no glass in it, yet they had weight. And then, starting at five minutes to two by the dashboard clock, I realized I was in an Edward Hopper painting. That is, everything I saw around me looked exactly as he would have rendered it.

The sensation persisted through bright sun and shadow, through fields and through towns lined with slant-lighted buildings. The people I saw looked like humanoid dolls—or, if seen from a distance, like the tiny people I bought in packages as a boy, to put in my model railroad village at Christmastime. By a lakeside, a solitary little boat parked empty at the end of a pier on the still water was so utterly Hopper, my scalp tingled.

Hopper is one of those artists whose pictures can do that to you: not just give you memorable images, but get you thinking and feeling that that’s the way it really is. My reaction was extra-powerful because shortly before the day of the drive, I had visited the Hopper exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art.

Close Encounters of the Hopper Kind

The show is called CMOA Collects Edward Hopper. There hasn’t been much media buzz about it, since most attention goes to the big blockbuster exhibits and this show is quite small, built mainly by gathering the Hoppers from the museum’s permanent collection into one room. How small? Two oil paintings, three watercolors, one charcoal drawing, and 11 etchings by Hopper, plus five etchings by other artists to show how they treated various themes compared to how Hopper did. Just 22 pieces total.

But visiting a small show has its virtues. It’s somewhat like a house concert versus a stadium concert. You can be close and intimate with the art, without having to shoulder-wedge or tiptoe-peek through the crowds that logjam in front of the ooh-and-ahh pieces at the blockbusters. A small show also doesn’t wear you out. You can fully absorb all of it, at leisure, then still have time and energy left to sample other attractions at the museum.

And Hopper is a perfect artist with whom to have an intimate, leisurely, close encounter. He lived long (from 1882 to 1967) and worked slowly, deliberating over every picture. Further, despite living through times of great turbulence and new movements in art—times when artists from Duchamp and Dali to Pollock and Warhol did work that would shock, provoke, and disrupt the art world—Hopper was never out to be Mr. Flamboyant. His pictures aren’t the kind that blow you away. They seep subtly into your veins. The show is a chance to let a few seep in.

As for saying a few words about a few of those pieces: Let’s deal first with the geometry thing. Much has been made of Hopper’s use of shapes and patterns, light and shadows, especially in his many pictures of buildings and other built structures. The show includes some fine examples of these. Looking at “Rocky Pedestal,” a stark watercolor of a lighthouse built upon rock— or at “Cape Cod Afternoon,” a big oil painting of a rambling old farmhouse, barn, and shed—one can almost think the structures were designed and built to be subjects of Hopper paintings that critics would someday rave about for their compositional values. (This shed ain’t gonna be no palace, boys. But step over here and take a gander at how the roofline will provide a shadowy yet sharp-edged counterweight to the sun-splashed peaks of the housetop.)

Now of course that’s not the real motivation. Architects and builders have their own reasons for wanting to make their buildings look good and they often succeed. But Hopper’s pictures are more than illustrations of cool architecture. They’re also more than geometric exercises in capturing neat interplays of shapes and shadows. A painter I once knew—not a famous one, but a very smart guy—used to say the best works of art meet two standards: They are technically excellent, and “they look like they mean something.”

Meanings out of Thin Air

To me, that tongue-in-cheek statement says a mouthful about a slippery subject. It is hard to talk about meaning in art with much certainty. Artists may or may not intend their work to convey particular, literal meanings, and even if they do, viewers will often find other meanings in it. Good art does however have some elusive quality or other that gets the wheels turning in a dimension beyond “ooh, that’s a pretty picture.” And Hopper’s art does that. It looks like it means something.

What does “Roofs, Washington Square” (reproduced above) mean? The text on the wall at the CMOA show says that the dense rows of chimneys and skylights in this New York rooftop scene “echo the urban chaos at street level.” I could buy that. But I’d rather, if we had the time, sell you my own interpretation. It comes partly from personal feelings evoked by the scene—which are tied to memories of hanging out on rooftops—and partly from the mood that’s cast by the light and air in the picture.

Hopper’s gift did not consist only of how he depicted his subjects, or even of how he depicted the light falling on his subjects. It’s how he was able to convey the quality of the light and the air themselves. This, I think, is a big part of what makes his pictures seep in and stay with you—because light and air are what we exist in, wherever we are. We feel them on our skin; we take them inside us; the air carries scents and sounds (and, yes, feelings and memories) … and to capture or at least suggest all of that in a flat, 2-D piece of visual art, well, that’s really doing it.

The Etchings, the People, the Endless Line of Ungulates

If you visit the show, try to spend some good hanging-out time with the smallest pieces, the black-and-white etchings. “Night Shadows,” reproduced at the top of this review, is the most famous but several others merit a nice long look. Some of them raise the oft-asked question: What’s the story with Hopper’s treatment of human subjects?

Many of his pictures have nobody in them. And in those that do, as noted earlier, the people seem android-like or ghostlike—or maybe there just incidentally, or somehow there but not all there. Is this supposed to be a statement about how we really are? In Raymond Chandler’s noir detective novel The Long Goodbye, a certain character is accused of being nothing but an act, and he replies: “An act is all there is. There isn’t anything else. In here, there isn’t anything.”

Some would describe Hopper’s art as being similarly, bleakly noir. I don’t know about that. See what you think. See what you think, for instance, of the etchings “The Lonely House” and “The Railroad.” The first shows an urban building on a vacant lot; the other is a shadowy trackside scene. Both offer a lot to look at—and a lot of lookers don’t even notice that there are people in these pictures.

Let me close by briefly describing my favorite piece in the show, an etching called “American Landscape.” It’s a scene of wide-open countryside with a railroad track, on a raised roadbed, slicing horizontally like a straightedge across the middle of the frame. On the far side of the track, poking up above it at one point, is a house: You can see the upper stories and the slanting sun on the roof. No people around. But there are cows. A line of cows on the march.

They’re coming in from the foreground, where you are—the closest one is just entering the frame at the bottom; you can see the back of its head and horns—and they are filing up across the track and down into the distance. Only a few are visible but there may be legions more up ahead, out of view, or following behind and yet to enter the picture. Shadowy legions upon legions of cattle.

What does it mean? Does it mean that the buffalo are gone, but still the ungulates prevail, and perhaps they will be here after we are gone? Once there were endless herds of bison, and now there is an endless line of cattle, stretching out to infinity …

Please excuse me. I’m getting carried away. Another Hopper flashback.

Credits and Visitor Info

CMOA Collects Edward Hopper was organized by Akemi May, an assistant curator at the museum. Through October 26 in Gallery One at Carnegie Museum of Art, 4400 Forbes Ave., Oakland. During October, there is free admission to the entire museum on Thursdays from 3 to 8 p.m. For other hours and ticket information see CMOA’s visitor webpage or call 412-622-3131.

Images courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer, covers visual art and theater for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter