The Revamped Warhol: More than an Art Museum, It’s a Theme Park of the Mind

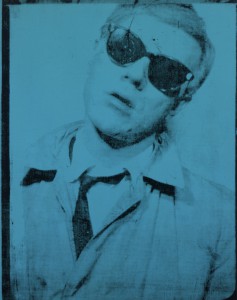

Oh, wow, Warhol seemed to be saying in his 1964 self-portrait. This year the Warhol Museum has re-done the thrill rides. (Image © Andy Warhol Foundation)

In a new documentary film about Andy Warhol, we hear from some of his old friends and colleagues whose memories have stayed keen. One is the painter Philip Pearlstein, deliciously droll on camera at age 90.

He met Warhol when both were art students at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon) in the late 1940s. Pearlstein already had a reputation on campus as a rising star. He recalls his eager and energetic young friend being perceived, with equal prescience, as a rising enigma.

Says Pearlstein of Warhol: “Everybody could soon recognize he had a special talent. Nobody could pinpoint what it was.”

The film is Andy Warhol: Fifteen Minutes Eternal. A little under 30 minutes long, it plays continuously in the first-floor screening room at The Andy Warhol Museum. And it’s among many new attractions the museum has added this year to mark its 20th anniversary.

The additions and changes—which include a re-hang of the whole permanent collection—go far beyond the typical rotating of the stock that most museums do. For a look at how and why the job was done, try our behind-the-scenes story. Here we’ll take an in-depth tour of the remade Warhol Museum from a visitor’s perspective.

From Silver Clouds to Sexual ‘Adjustment’

One thing has stayed constant since The Warhol opened in 1994: It has never been just another art museum. Given the nature of the work that Warhol did—so many different kinds of art; so much of it bizarre—the place has always had the feel of a giant indoor theme park, with various zones of amusement or bemusement. The new twists at the museum bring out this quality more sharply than ever.

Some popular features have been kept, like the “Silver Clouds”room, where children (and adults) can have a ball batting around the shiny pillow-shaped balloons. Notable new areas include the Exploding Plastic Inevitable room, which simulates the multimedia rock-music events of the same name staged by Warhol in the 1960s.

Better yet is the new Film and Video Gallery. Touch-screen consoles are installed so that visitors can browse at will through Warhol’s own creations for the screen. These run the gamut from sort-of-mainstream, such as his pre-taped 1981 comedy segments for “Saturday Night Live,” to early black-and-white films that deserve an “I” rating—as in Idiosyncratic, Inappropriate for children, perhaps Inscrutable or perhaps Inspired.

A rarely seen 1968 film, The Loves of Ondine, stars one of the memorable characters who frequented Warhol’s Manhattan studio. Ondine (born Robert Olivo), who was gay, portrays himself, except that in the fictional story line he’s trying to go straight. The satirical film is highly improvised and tends to ramble, but there are sterling moments.

In a classic battle-of-the-gender-identities scene, the dashing, dark-haired Ondine tries to persuade a young woman to remove her clothes. The woman, Pepper Davis, demurs. But Ondine, seated close to her and mesmerizingly shuffling a deck of cards, presses ahead in a perfect deadpan: “You could be a real service to me. I don’t like living in the homosexual community … You could help me adjust. You could be my knob.”

Some fun. And, like much of what’s in the Warhol Museum, it is fun that raises questions.

Whose Leg? What Does It Mean?

In Warhol’s work you often aren’t sure whose leg he is pulling: yours, his own, no one’s, or society’s collective leg.

The “Saturday Night Live” segments offer a mixture. Here we get Andy himself, surprisingly chipper and bubbling into the camera. Referring to a well-known fashion magazine, he chirps, “I heard you have to sleep with somebody to get on the cover. And, uh, I’m willing to do that.” (High school essay writers, take note: This line pokes fun at the stereotype of Warhol as a crassly commercial trickster who would “prostitute” himself for publicity’s sake.)

Then Warhol turns the tables. Claiming that he personally hates “Saturday Night Live”and never watches the show, he peers into the lens to ask a nation of viewers: “Why are you home on a Saturday night?”

Then again, some might ask: Why spend a day at the Warhol Museum? There are legions of Warhol deniers—people who may get a kick out of his kicky stuff like the cloud balloons or the cow wallpaper, but consider him mainly a cheap-thrill artist and deny that his art has any real significance. Even more people are curious but puzzled. What does all of this mean? Am I getting it? Where was the guy coming from, if anywhere?

What I, for one, like best about the 20th-anniversary Warhol Museum is that the galleries are redone to address such questions at just the right level. They don’t squeeze the life out of the art by providing loads of easy “answers.” They do provide new insights (and recurring glimmers of insight) that can lead to a-ha moments you might not have had before.

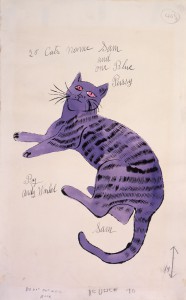

Cover sketch for Warhol’s self-published book “25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy.” While building his career in the 1950s he gave copies of the book to friends and influential people. (Image © Andy Warhol Foundation)

A Strong Mom and a Nose for Fame

Start by riding the elevator to the top floor, the seventh, which has been turned into a mini-museum of Andy Warhol’s early life and work. Old family-and-friend photos, mixed with selected artworks, take you step by step from his Eastern European roots and Pittsburgh beginnings through his move to New York and initial rise to fame in the 1950s to early ‘60s.

One can see many patterns emerging. There are vivid glimpses of Warhol’s mother, Julia, who played a prominent role in her youngest son’s career. A replica of her 1920 passport photo, taken before she came to the U.S. from present-day Slovakia, shows a bright-eyed young woman looking bold in a babushka. She’ll turn up again and again later.

Silly patterns emerge as well. Born in 1928, Warhol grew up in Pittsburgh’s South Oakland neighborhood, and among the many photos of him with his two brothers, his parents, and other folks is a large-group snapshot. Andy is thought to be a certain toddler in the foreground, but the boy’s face is obscured by his hand. He is picking his nose with manifest intent.

Next, cut to the artworks from Warhol’s student days at Carnegie Tech. One is a grotesque drawing of a man engaged in the same pursuit. The sketch led to a painting he called “The Broad Gave Me My Face But I Can Pick My Own Nose.” Then look at the text-and-photo panel on another wall that highlights events throughout Warhol’s formative years. You learn that in 1957, in New York, the now fast-rising artist had minor cosmetic surgery: a nose job. He picked his own nose.

But here on the top floor as well as on the floors below (which take you down through Warhol’s later periods in chronological order), what’s on display is not all self-obsession. The themes and subjects branch out dramatically.

A Painter of Icons

One recurring pattern appears to have very deep roots. Warhol was raised a Byzantine Catholic. The church he attended throughout his youth, St. John Chrysostom in Lower Greenfield—the one with twin steeples near the bend in the Parkway East—is, like many Byzantine churches, filled with painted icons.

And what did Warhol paint, photograph, or otherwise render in a lot of his art, as he grew into middle age? Icons—the secular icons of a tumultuous America in the mid-20th century.

After graduating from Carnegie Tech in ’49, Warhol began his career in New York as an illustrator for fashion advertisements. The museum has mounted a nice exhibit of his work in that field. Hanging nearby are samples of his early independent work, for art shows and gallery sales. In both areas one can see him giving iconic treatment to subjects that were of great interest to advertisers and the public alike. Products.

During the postwar boom years, the U.S. was suddenly awash in consumer products. People couldn’t get enough of them. And Warhol painted and silk-screened their images, in a multitude of styles and in scales from the life-sized to the heroic. Telephones. Shoes. Coca-Cola and canned soups. Guns …

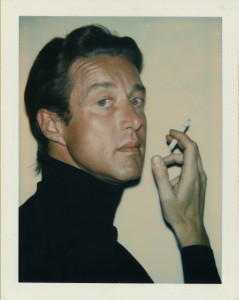

Polaroid “instant” cameras were used mainly for getting on-the-spot snapshots, but Warhol also used them to make portraits, including this one of the designer Halston in 1974. (Image © Andy Warhol Foundation)

He painted, photographed, and otherwise rendered iconic people, too. People so iconic that many could be identified without their last names, like Marilyn and Jackie. Liza. Elvis. Mao. O.J. Arnold. Be sure to catch the wall of Polaroid portraits on the fifth floor.

This floor also has an installation of Warhol’s big so-called double portraits. He would make multiple portraits of someone by starting with a photographic image, enlarged and silk-screened onto a series of canvases. The canvases would be inked (and often spot-painted) in various bold colors to highlight particular aspects of the person. When a pair of such portraits are hung side-by-side, as they are here, you get twinned images of the subject. The effects can be striking.

Take, for instance, the double Truman Capote. Made from the same original image, the two portraits show the writer posed identically in his trademark fedora hat, with a cigarette. The coloring is different in just one respect: Capote’s hat is bright yellow in one panel and red in the other. But what leap out are the twin pairs of eyes, all treated the same. Splashed in a vivid light blue, his eyes are piercing and yet frighteningly vacuous. (Sorry, Truman. That’s how it looks.)

Julia Warhola, Andy’s mother. He made this portrait two years after her death and it now hangs as part of a pair in The Warhol. (Image © AWF)

Perhaps the most moving double portrait is of Warhol’s personal icon, his mother. Julia had lived with him in his New York townhouse for many years until shortly before her death, in 1972. Warhol made the portraits in 1974.

While both panels are washed in colors, the outlines of the matronly image are clear and full in the left-hand panel … whereas the right-hand image is dramatically different. Black and eerie blues have crept in from the edges, blurring the outlines and blotting out parts. Julia is being subsumed into the Big Wash. Amen.

After seeing pictures like these, you may not agree with the skeptics who say that all Warhol did was copy photos and jazz them up.

Snoozes and Raincoats

But you don’t have to agree, either, with hardcore Warhol fans who find profound significance in everything he did. I know someone who knows someone who claims to have watched all five hours and 20 minutes of Sleep—Warhol’s 1963 film of a man doing what the title says—and who calls it a cinematic masterpiece. Well, maybe it is. You can come to the Warhol Museum and have a look for yourself.

Nor is every feature of the new, updated museum a total success. By all accounts, Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable concerts were incredible when experienced live. They had the Velvet Underground soaring to sonic limits amid the blazes and shimmers of lights by light-show pioneer Danny Williams. There were dancers and pantomime actors egging on the shoulder-to-shoulder crowds of live people, many of them in highly exalted states of consciousness.

The museum’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable room strives to emulate the effect with multiple wall-sized projections of films from these events, plus piped-in sound and some flickering lights. It’s definitely better than watching the grainy film clips posted on YouTube. Compared to any good live concert, though, it’s a bit like taking a Sixties shower in a raincoat.

The Bunny and the Beehive

However the museum has surprise hits as well. One will only be on view through August 24, a special exhibit titled Halston and Warhol: Silver and Suede. The fashion designer Halston (born Roy Halston Frowick) was Andy Warhol’s good friend and occasional collaborator during their mutual heyday from the 1960s into the ‘80s. The exhibit has clothing and hats by Halston mixed with related works by Warhol—which, to someone who’s not a fashion maven, may sound rather uninteresting. It is anything but.

For one thing, individual pieces in the exhibit are darned good. Halston knew what he was doing. Do you care to see the fur-trimmed gown and bunny mask that Candice Bergen wore to the marvelous Black and White Ball at the Plaza in 1966? Maybe your shot-and-a-beer uncle would take a pass, but I’m tellin’ ya both, it’s worth a look. The bunny mask is spooky … in a beautiful way. And many of the garments (some incorporating Warhol design motifs) are eye-catching in the gracefully flowing, deceptively simple way that was Halston’s signature.

This evening dress by Halston incorporates the design motif from Warhol’s flower paintings. (Image courtesy Indianapolis Museum of Art)

Also, the Halston and Warhol show neatly conveys the fact that no artists work alone or in a vacuum. It’s well known that Warhol worked (and played) surrounded by crowds of acolytes and lesser lights—hey, he was from Pittsburgh, so no wonder he made himself CEO of a mass-production art studio called “The Factory”—but in Halston and Warhol, you get to see him interacting with an artistic peer.

Videos and photos show the men combining their acts to make joint works, and hanging out together with their friends (such as Liza Minnelli, who wore clothing by Halston, posed for portraits by Warhol, and partied with both). Not only can you detect common threads in their art, you get a tangible sense of where art comes from: how it imitates life as well as vice versa, how artists both reflect their times and create them; how it all happens in a beehive jumble and then continues, evolving over time.

As for the significance of Warhol, he neither created nor reflected everything around him. At any period in time there are many, many influences. But at the least, it should start to be evident that a lot of what’s on the Internet today carries DNA strands passed on by Warhol.

Wrapping It Up: Gunshots, Cokes, and Elvis

A final surprise at the Warhol Museum is a new area called The Office. At first glance it looks like a mundane conference room: a long table with chairs, in a room with photos on the walls. Step inside. The Office is ideal for a last stop on one’s museum visit, or a midway interlude.

There are photos not by Warhol, but of Warhol, and some are staggering. In one, his shirt open to reveal the many scars on his torso from life-saving surgeries after he was shot by a deranged gunwoman, Valerie Solanas, in 1968.

The table has a collection of books by Warhol. These were typically co-written or ghostwritten with the help of his longtime assistant, Pat Hackett, and they can be browsed for gems of wisdom or whimsy. You can find plenty of crypto-Zen zingers, like his response to being asked if he ate fast food: “No, I eat food fast.”

The book POPism has some nice material on the Pop Art aesthetic as Warhol saw it. And The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) includes famous passages like his paean to a product, Coca-Cola:

“What’s great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest … A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good.”

All 11 Elvises are sort of the same, too. Perhaps their power lies in their massive togetherness. A great delight of any museum is just being randomly surprised by something that grabs you, and taking the time to look at it. On a recent visit to The Warhol I noticed a young woman sitting transfixed in front of the silkscreen painting “Elvis (Eleven Times).”

This is a silver-and-black monster, 36 feet wide. Across it stand 11 life-sized Elvis Presleys, each one facing you resolutely, pointing a pistol. (The core image was a publicity photo from the Western movie Flaming Star.) I don’t know if the woman was transfixed by awe, dread, or bafflement. I can report only that she was staring at Elvis, Elvis with a gun, a gun; Elvis, Elvis, Elvis.

And so the beat goes on at The Andy Warhol Museum, now 20 years into its mission of being a theme park of the 20th-century mind. The feature attractions all come from the fertile and enigmatic mind of a single artist. Visitor experience will vary. The ride you get will depend on the mind you bring.

Mike Vargo is a freelance writer and editor based in Pittsburgh.

Share on Social Media

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter