‘Revelation,’ at The Warhol, Reveals Andy’s Spiritual Journey

An early devotional work: Andy was between 10 and 13 years old when he painted this store-bought white plaster statue.

The best answer to “What was Andy Warhol really like?” is “How much time you got?” Much has been written and said about Andy, but no simple profile emerges. For years he lived a divided life in New York City, sharing an apartment with his elderly mother while using his studio to make films like Blow Job and Taylor Mead’s Ass. Friends and associates described him as self-conscious and guarded, but also compelling and charismatic. Among them he earned the nickname Drella—part Dracula, part Cinderella.

Given such ambiguity, trying to discern how Warhol’s art reflects the man himself can be an adventure. One biographer, the poet Wayne Koestenbaum, analyzed Andy’s Pop paintings as follows: “… each canvas asks: Do you desire me? Will you destroy me? Will you participate in my ritual? Each image, while hoping to repel death, engineers its erotic arrival.” Perhaps you never saw these implications in pictures of canned soup and Coca-Cola. Now you can look for them.

And now, at The Andy Warhol Museum, you can see another aspect of Andy’s psyche on display. The special exhibit Andy Warhol: Revelation (extended through March 1) is worth a visit for anyone with an interest in art, or religion, or spirituality. It’s billed as “the first exhibition to comprehensively examine the Pop artist’s complex Catholic faith in relation to his artistic production.”

Revelation indeed aims to be comprehensive. The show packs a lot of intriguing art into a cluster of relatively small gallery spaces, which also hold artifacts and mementos from Andy’s life. Near the entry are icons of four saints that stood in the Pittsburgh church he attended as a child, during the 1930s. Another gallery has photos and souvenirs of his 1980 visit to Pope John Paul II in Rome. (Warhol, known worldwide by then, thought he’d been granted a private audience with the Pope. But the documents he was issued only put him among multitudes of people lined up for a brief walk-by greeting. Forget 15 minutes of fame; you’d be lucky to get 15 seconds of papal face time. It seems Andy took things in stride and made good use of his turn, giving John Paul II a hearty hello.)

The mementos are interesting. Along with the narrative text panels throughout the show, they trace a life’s story running from Andy’s boyhood in a deeply religious home to his last major artworks—a series of riffs on Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper”—which he made shortly before dying, suddenly, at the age of 58.

Andy’s doubled-in-pink ‘Last Supper’ looks tiny here but spans a wide wall in the gallery.

The Revelation exhibit, though, is more than biographical. What you come away with is more than a sort of Portrait of the Artist as a Guy Who Had a Religious Side. There is art in the show that speaks to everyone’s religious side, including to folks who don’t think they have one. The art should resonate with any person who has felt or desired a connection with—or questioned the existence of—a power and realm beyond our material world.

A Byzantine Backstory

Warhol was raised Byzantine Catholic, a branch of the faith in which most churches are lavishly decorated with painted icons and such. Andy’s home church, Saint John Chrysostom in lower Greenfield, certainly was (and still is), which has led to one line of commentary about his religion vis-a-vis his art. In essence it says: The impressionable boy saw icons all over the place, so no wonder he grew up to paint secular icons, such as products and movie stars.

True as far as it goes, maybe. There’s more to the story. Maybe the boy actually had what people call religious experiences, and maybe they stayed with him. Warhol’s peak years as an artist, from the 1960s on, were a time when many Americans drifted away from organized religion. Warhol didn’t drift clear out to sea; he kept revisiting the shore.

Often he’d show up at a church in Manhattan, sitting unobtrusively in the back and staying for only part of the Mass. Sometimes on holidays he’d turn up publicly to volunteer at a feed-the-needy dinner. His diaries and records don’t speak of fundamental issues of faith, but they do note other acts of religious interest and benevolence. Was he merely a Pascal wagerer—the philosopher Blaise Pascal said it’s a safer bet to stay on good terms with the Almighty, just in case He exists—or did Andy genuinely continue searching for a spiritual spark? The art in Revelation suggests the latter.

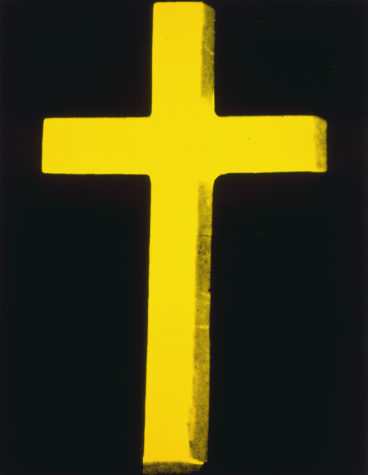

In the ‘Revelation’ show, Warhol’s large yellow ‘Cross’ is paired with a red one. Together they bracket one of his ‘Skull’ paintings.

Money Shots, Death Masks, a Better Body

Nearly all the art is in Warhol’s signature style, consisting of images from other sources that he appropriated and altered. His “Last Supper” series was done on commission, for a gallery owner, but it’s fair to say Andy exceeded the call of duty. He produced around 100 separate pieces and Revelation includes several. The big one is a bright pink, side-by-side double copy of the classic picture, 25 feet wide, spanning an entire gallery wall. There’s also a gripping smaller piece that homes in on a key detail: the traitor Judas, clutching his bag of bribe money.

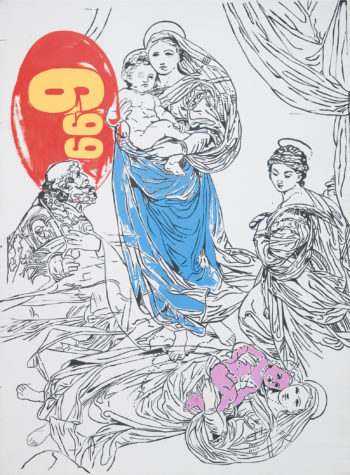

The holy figures in ‘Raphael Madonna—$6.99’ are from the Renaissance painter’s ‘Sistine Madonna’ and the cash figure is from a 20th-century ad.

Another “money shot” hangs outside the main exhibit space. “Raphael Madonna—$6.99” is a composite, with a price tag slapped on Raphael’s masterpiece, and one could take it as a satire of the commercialization of the sacred. (Although it’s probably worth tons of money itself, and Warhol liked money. Thinking about it in those terms can either lead you to appreciate the multiple meanings in art, or help you understand why art critics go dizzy when they write.)

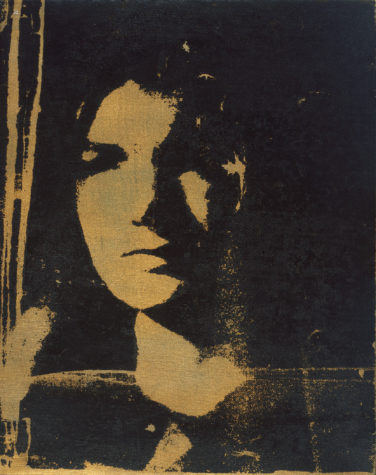

JFK’s widow becomes an icon of mourning. This 1964 ‘Jackie’ is one of a series in the exhibition.

Some of the strongest pieces in Revelation don’t have explicitly religious themes—unless you consider death a religious theme, as we mortals tend to do. Warhol had a lifelong obsession with death and the show includes a gallery I’ve dubbed the death room. On one wall are multiple altered images of Jacqueline Kennedy, from a news photo taken after her husband’s assassination.

Another wall features a ghoulish series of Marilyn Monroes. Warhol started doing Marilyns right after the actress’s untimely end. The images on this wall are printed in black-and-white negative fashion, so they make her sensuous face go dark, darker, and obscenely blurry-black as you walk along the array.

Cheerful stuff, eh? Other pieces are livelier, emitting rays of hope or at least hopeful inquiry. Andy had to reconcile his spiritual inclinations with the fact of being gay, which was anathema to his religion of birth, and Revelation has a section of artworks exploring the subject. One large piece is, like the “Raphael Madonna,” a pastiche. Warhol copied an image from a bodybuilding ad—a virile bare-chested man, under the headline “Be a Somebody with a Body”—and combined him with three images of the face of Christ, lifted from the “Last Supper.” The piece practically asks, Can’t these go together?

To me, a non-gay man, the piece came across as not only about sexual identity but about human identity, period. It called up a memory of a friend now deceased. You might’ve judged him a head-in-the-clouds philosophical type, except that philosophy’s basic questions about the nature of being (and the nature of the Supreme Being) were, to this friend, painfully personal. He agonized over the question of what he was. And, as I studied “Somebody with a Body” parked next to triple Jesuses, it reminded me of the closest my late friend came to an answer. One night, near the end of a rambling, circular conversation about matters such as mind-body duality, he looked hard at me and said “I’m not a man with a soul. I’m a soul with a man.”

Two Striking Pieces and a One-Liner to Go

Andy’s 1967 “Sunset” film, with words by Nico, delivers a slow-motion soliloquy.

The piece at the front of Andy Warhol: Revelation is a 33-minute film segment made for a Catholic exhibition project that didn’t pan out. Like many of Warhol’s early films it is slow, inviting contemplation. In a recurring loop, on a sizable screen, you watch the sun set. Colors of the sky and shades of the light shift oh, so gradually, ever darkening. The soundtrack is the singer Nico whispering, not singing, what seems to be a prose poem or a vocal meditation. “We are always alive. We are always … [silence] … Death wants to be here …”

And so forth. The film is arrestingly eerie. Unfortunately the screen is mounted at the very entrance to Revelation, facing into the hallway where people are milling and talking. If space had permitted, “Sunset” would’ve been better in a dark room of its own.

A favorite piece inside the show needs no help. The big, bold painting is a dramatic alteration of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Annunciation,” now preserved in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. We don’t have a press photo of the Andy-ed version so please make do with my description.

Leonardo’s original painting shows the angel Gabriel on the left announcing to Mary, on the right, that she will give birth to the boy Jesus. The composition is understated but dynamic. Gabriel fixes his gaze on the young woman and puts forth a hand in benediction, as if beaming a holy force field her way. Mary seems to receive the sacred charge willingly—although one feature strikes an uncertain note, and Warhol used it.

Warhol’s painting crops out both figures. All we see of them are the angel’s hand reaching into the frame from one side—disembodied, but in a gesture clearly meant as a blessing—and ‘way over on the other side, Mary’s extended right hand. Which does not display receptivity or connection. That hand is placed on a book (a book of Scripture?), restlessly fingering the pages, as if searching for documentation of what’s up. In Warhol’s version the distance between the hands is vast. He’s even accented the gap by coloring the sky blood-red, which highlights a mountain looming in the background.

This picture mesmerized me. I kept circling back to it. As I interpret it, it evokes the irony of spiritual frustration. The spirit is out there, looking for us, but we grope and miss because we’re looking somewhere else.

Of course others may interpret the picture, or the whole show, differently. That’s fine. Art is food for thought, not diagrams of what to think. If you want to augment your visit with some reading, try the catalogue book for Andy Warhol: Revelation. The museum’s gift shop has copies you can buy or just browse while sitting in an easy chair.

The book’s feature essay is by Miranda Lash, a curator at the Speed Art Museum in Louisville (where Revelation will go after it closes here). One short bit from Lash’s piece leaps out. She relates a time, in 1977, when someone asked Andy if he believed in God. His reply was both typically Warholian, and the kind of answer that many people might give: “I guess I do.”

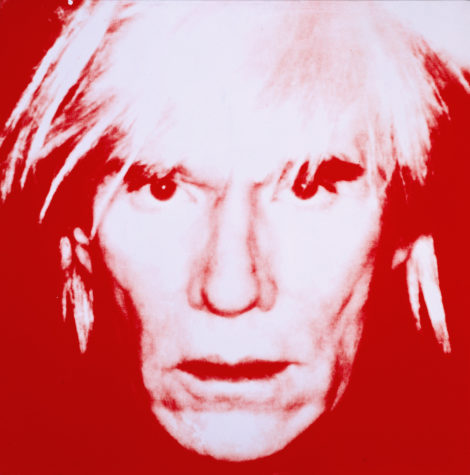

Are there visions of mortality in Warhol’s 1986 ‘Self-Portrait’? Andy died the next year.

Notes from Behind the Scenes + Visitor Info

The Revelation exhibit was created by José Carlos Diaz, chief curator at The Andy Warhol Museum, and it evolved from planning for a show that could’ve happened in Rome. Diaz said that in 2017 he’d been pondering ideas for “exhibitions about lesser-known aspects of Warhol”—including Andy’s religion—when the museum was contacted by Micol Forti, curator in charge of modern and contemporary art at the Vatican Museums. “She was interested in researching this area, but also working on an exhibition, so I quickly thought it would be great to get involved.”

Diaz met twice with Forti in Rome, conceptualizing what the show might look like: One thought was mixing Warhol’s religious art with works from the Vatican’s renowned collection of Old Masters. But the project “never got beyond the brainstorming phase,” Diaz said. Last year the overall director of the Vatican Museums announced it wouldn’t be done, citing other commitments. Diaz then proceeded with developing the exhibit you can see at The Warhol.

“The show is for everybody,” he says, churched or unchurched. It also includes subtle touches in exhibition design from Diaz and independent designer Jacob Dyrenforth. For instance, if you turn left on entering Revelation, you’ll go through in an order that follows Andy’s life from birth to final works. And whereas the “Sunset” film at the front depicts light fading to darkness, the gallery spaces get ever brighter as you go.

Andy Warhol: Revelation continues through March 1 at 117 Sandusky St., North Side. The museum is open 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. most days and until 10 p.m. Fridays; closed on Mondays and major holidays. For more information, including news of public events related to Revelation, visit The Warhol on the web or call 412-237-8300.

Image and art credits: Painted statue of Jesus Christ, collection of Jeffrey Warhola. “Sunset” film, © The Andy Warhol Museum. All others: © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer, covers visual arts and theater for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter