Making a Statement, Living the Statement: Quantum’s ‘The Return of Benjamin Lay’

In our politically charged times, a lot of politically charged works are being produced in the performing arts, and not everyone is happy about the trend. A common complaint is that artists and the groups that present them have begun to value social commentary over aesthetic quality—giving us stuff that rings all the right bells in terms of relevance, but falls short of being good.

You should not have that problem with Quantum Theatre’s The Return of Benjamin Lay (through February 23). The play is a wonderful paradox. It comes at you with a thunderous barrage of moral messaging, and yet at the same time it’s intricate and personal, dancing across a keyboard of emotions, from hearty amusement to angst.

Much credit must go to the co-writers, the U.K.-based playwright Naomi Wallace and Pitt history professor Marcus Rediker. Along with actor Mark Povinelli, who performs the play solo, they have applied their skills to a great subject. Benjamin Lay was a real person. And what a person he was. A man intent on making a statement, he lived and practiced what he preached—provoking reactions that ranged from puzzlement to outrage in the people around him.

The Real Benjamin

The 1700s were turbulent times in the Western world. The century’s first half was a sort of hinge period between methods and mores of the past and the emergence of proto-modern ways: an era when civic tensions that had been heating up for ages began rising to full boil. Benjamin Lay (1682 – 1759) entered adulthood as one of the more restless souls on the scene. Born in England to a family of Quakers—one of many breakaway sects from the established church— he tried farming and shepherding, then took apprenticeship as a glove-maker, then scooted off to sail the wide seas as a crewman on merchant vessels.

After 12 years of that he jumped ship back home to marry a Quaker woman. He and Sarah tried settling as shopkeepers in Barbados, then an English colony. But they were appalled by what they saw. Barbados was a slave-labor hellhole where wealthy planters beat and tortured imported Africans if they slipped in the slightest from the grueling work of turning sugar cane into sugar.

Seeking a humane haven, Benjamin and Sarah set out for the Quaker-inspired colony of Pennsylvania, landing in 1731 at Philadelphia. And Benjamin was doubly appalled to find that many of his fellow Quakers owned slaves. Thus began a fiery career of full-bore activism. The Society of Friends was in those years just starting to be gradually, gently nudged toward the abolitionist views it would later champion. But gradual and gentle weren’t his style.

Benjamin Lay was a drama king. He dashed off a hell-raising book—edited and published by his friend Benjamin Franklin—emphatically titled All Slave Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates. He stormed into Quaker meetings and performed street-theater-type stunts to drive his point home. Among them was one in which he hid a pouch of berry juice inside a hollowed-out Bible, whipped out a sword, and pierced the Bible, spattering blood-red liquid over the congregation members nearest him. Eventually Lay was drummed out of every Quaker meeting in the vicinity, warned never to return.

Except that now, in the realm of theater, he does.

Lay in the Play

The Return of Benjamin Lay is premised on a bit of audience participation. When the lights come up and Mark Povinelli appears onstage as Lay, speaking and gesturing directly to the audience, it quickly becomes clear what’s up. You are to imagine that you’re seated among an assembly of Quakers gathered to hear him make his case for readmission to the fold.

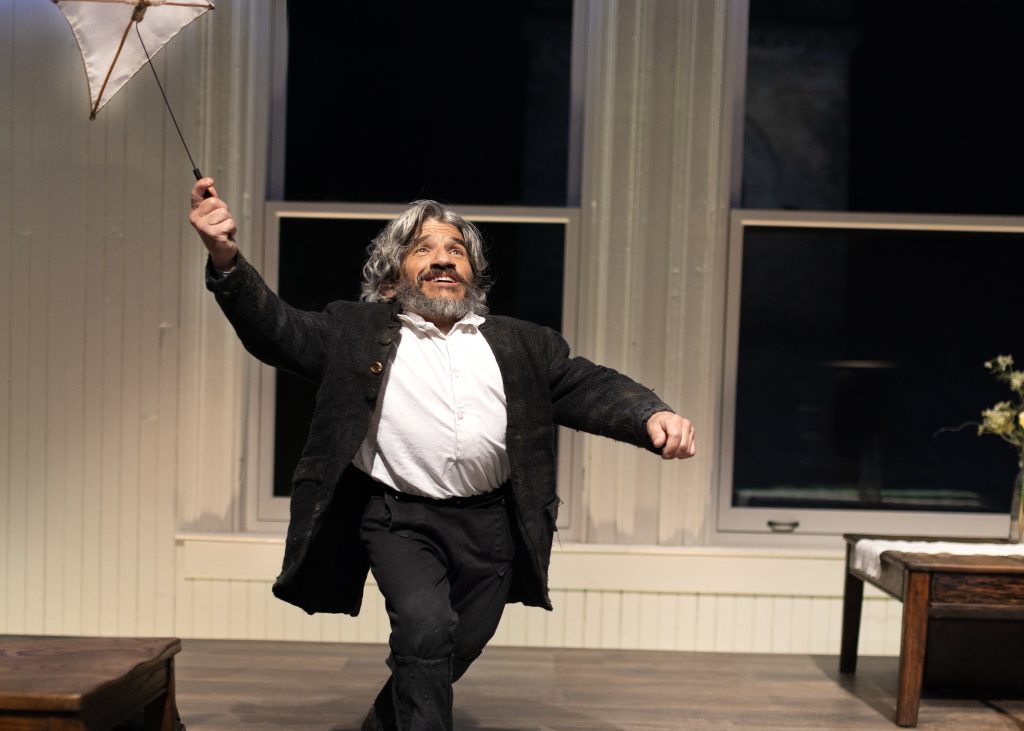

And here is what carries the play far beyond heavy-handed rhetoric. Lay does much more than simply stand there rehashing his theological and moral arguments against slavery. He decides that in order to really get where he’s coming from, you need to absorb his life’s story. So he tells it and acts it out. Visibly absorbed, himself, in what he’s doing, he re-lives the high points—from his days as a bold sailor, climbing a mast to mend the sails and the rigging (a high ladder is used for this part), to the blood-spattering Bible stunt (relax; the spatter won’t reach even the front row) and more.

Lay re-lives the low points, too. It’s fascinating to watch him alternate between spells of gleeful macho bravado and deep spiritual sorrow. At one point he gravely invokes his horror at watching the torture of a slave who’d befriended him. And there are times when he mourns how much he misses the transcendent fellowship of Quaker meetings—the times when, he says, “the essence of God’s love pours down into me.”

Again, the alternation of moods is engaging. This Benjamin can switch, in a flash, from preaching to pleading (just as we all do, sometimes). Throughout the play, there are just enough interludes of humor and merriment to keep things a-bubble. And throughout, there’s an element that adds another level to the drama.

The real Benjamin Lay was a little person, today’s polite term for a dwarf. So is actor Povinelli. Watching him as Lay, you begin to get glimmers of how it feels to be radically different from—literally, smaller than—most other people, and how it’s possible to not let that limit you.

As the play goes along, taking you on a multi-level roller-coaster ride, it builds to a crescendo. When Lay mounts his closing arguments, urging the audience to speak and act out not only against human bondage, but against cruelty to animals (Lay became a strict vegetarian) and all other forms of cruelty—when he invites you to let God’s love and justice roll down on you—it is genuinely moving.

At the end, on the night I went, the audience rocketed up in a standing O punctuated by shouts and woo-hoos. I left the theater feeling moved to be, if only in some small way, like Benjamin Lay.

Closing Credits and Ticket Info (+ more)

Naomi Wallace’s and Marcus Rediker’s The Return of Benjamin Lay is directed for Quantum Theatre by Ron Daniels. He previously directed for the Royal Shakespeare Company, and directed Mark Povinelli in the world premiere of Benjamin Lay in London in 2023. Quantum’s U.S. premiere is staged on the top floor of the historic Braddock Carnegie Library building. Through February 23 at 419 Library St., Braddock. For tickets and further information, visit Quantum on the web.

Scenic and costume design is by Isobel Nicholson, with lighting by Anthony Doran (in conjunction with C. Todd Brown, the company’s resident lighting designer), and sound by John Leonard. The director of production is Alex Ungerman; the technical director is Cubbie McCrory, and the stage manager is Cory F. Goddard, assisted by Nathan Walter.

Furthermore, if you are inspired to read about the subject—either before or after the play—try Marcus Rediker’s book The Fearless Benjamin Lay, which was the basis for the stage production. And a transcript of a lively lecture given by the author is available for free on the web.

Photos by Jason Snyder.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer and editor, writes about theater for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter