‘Wicked’ is Unlimited Joy and All for the Good

On the professional stage, developing the full arc of a character’s transformation from beginning to end is a challenge rarely met. Not until the advent of modern theatre did playwrights even attempt to make character transformation the centerpiece of their limited time in which to tell a story. Two hours, more or less, is a short window. And so, traditionally, character arcs were dramatized only as rather sudden self-realizations. The classic example is Nora in A Doll’s House. The play by Henrik Ibsen was iconoclastic, a culture-shattering story which follows the humility of a young bride whose secret misdeeds have saved her husband from public scandal. But Ibsen spoke truth when, instead of Nora throwing herself at the mercy of her husband or, as we might have anticipated, committing suicide, she does something completely unexpected. She just walks out the door. The hell with marriage and playing the dutiful housewife. To contemporary audiences, that final door slam doesn’t sound terribly dramatic. But it changed everything in modern theatre. Suddenly, the fascination of character-driven storytelling focused on how the protagonist’s motives change from beginning to end. What made Thelma & Louise drive off a cliff? Weren’t they just out for a weekend of fun? Wasn’t Kate Winslet happily engaged to be married when she boarded the Titanic? Why would a wealthy Osage widow marry a short, white cabdriver? Of course, women who discover their own bravery in the span of a two-hour drama are no longer rare. Which makes the story of Elphaba in Wicked something extraordinary. And it’s a transformation that delivers tears of absolute, indelible truth.

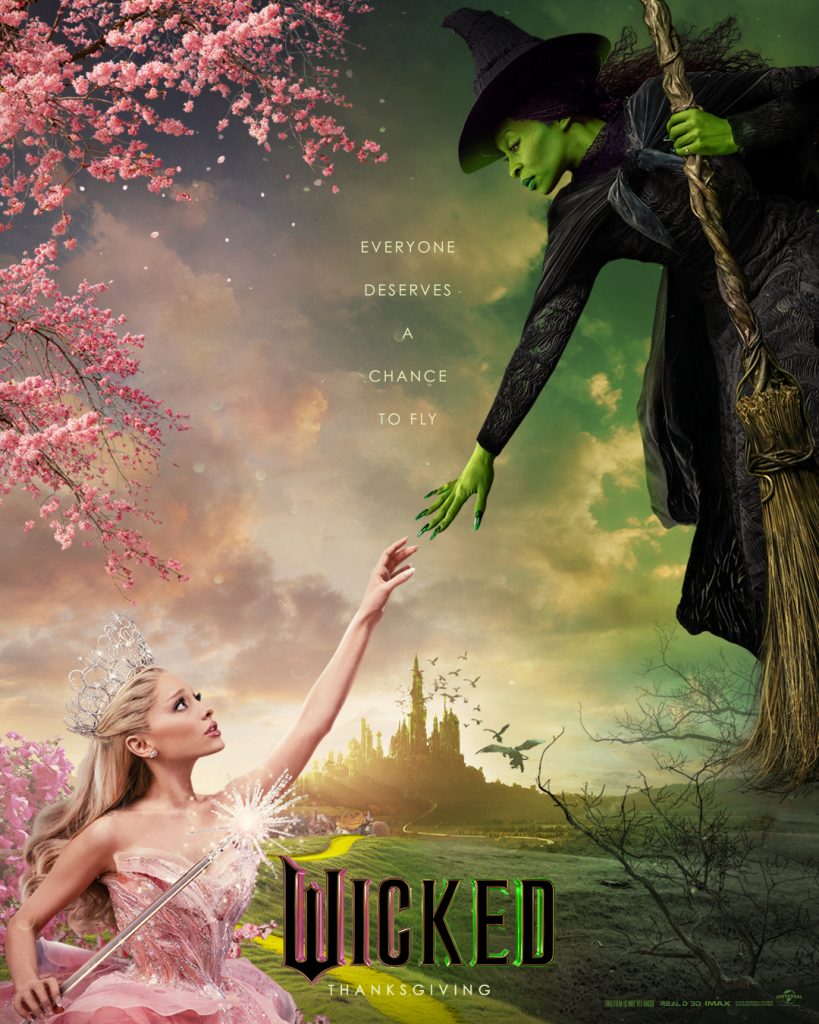

Of course, most “wick-heads” clamoring to see this new film adaptation of Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holman’s hit musical (loosely adapted from the novel by Gregory Maguire and which, of course, is based on L. Frank Baum’s original story which inspired the all-time MGM classic film starring Judy Garland) may be more interested in hearing new voices sing their favorite musical. But Director Jon M. Chu and his team of exceptional production artists have uncovered the rarest of gold in bringing Wicked to the silver screen. And, while, without hesitation, Ariana Grande makes an inspired Glinda, it’s our time with Elphaba, played, embodied, and given new life by Cynthia Erivo, that reveals an entirely new reason to love this fantastic, and fantastical, musical. Wicked, brought to the screen, is a masterpiece. Yet, Chu and his team—by exploring Elphaba’s singular character arc—have created one of the most powerful films in cinema history.

There are so many great elements to this production it’s hard to know where or in what order to explain. Okay, let’s just start with Cynthia Erivo. Her voice is pure mephistophelian magic, and it’s emotional, measured and, yet, immediate. Unlike any other musical before this, Erivo makes no concerted effort to mask that awkward stage segue between delivering lines and singing her thoughts. There’s not a hint of this polished performer taking a deep breath, breaking the pace, glancing misty-eyed to the sky and then delivering lyrics which transcend the reality of the moment. Cynthia Erivo is never for a millisecond less than 100 per cent focused. From her first note of “The Wizard and I” she hooks the audience until the very last frame. (But, if you didn’t already know it, this film adaptation of Wicked is just Part One; hold on to your witch’s hat for Part Two next year!)

Perhaps the greatest advantage the film has is the pacing of the story. We know from the stage musical how exhilarating it all is. But now, because we have the benefit of a Part I alone to fill two and a half hours, director Chu gives us some breathing room to better understand both the backstory and the events happening in the present. It’s hard to say anything critical about the stage musical, but, in retrospect, the filmed Wicked makes us realize how jam-packed the exposition of the stage musical truly is. How refreshing it is to experience the horrific moment of Elphaba’s birth, how shunned she was in the garden of her youth, and who it was that gave her the love to carry on, despite the many injustices both bigotry and belonging thrust upon her.

And that very pacing is what gives us the necessary time to deeply appreciate Elphaba’s character arc. She is a sympathetic sister, duty-bound and nearly stoic in deflecting the many prejudices of being born green, grotesque and forgotten. That prejudice is what drives the entire story of course. Elphaba’s empathy for Dr. Dillamond is driven by her very personal understanding of prejudice without reason. Even when Glinda invites Elphaba to the dance wearing a hideous hat, we all feel the embarrassment of being made a fool in front of hopeful friends. But what really makes Elphaba a character driven to right wrongs, to act with moral altruism—to be the good person we want her so desperately to be—is absolute, earth shattering betrayal.

And that’s what makes Elphaba’s character rare in dramatic storytelling. It’s not just that she is to be pitied for what she’s already suffered, she is now a hero whose good has been betrayed. That’s a whole level above and beyond what any audience needs in order to relate emotionally with a character. We’ve got two really compelling reasons to love her. And, boy, does that love erupt from deep emotions. If the stage version was meant to allow us the tears that the film version swells up, there was too little time for it. Bring tissues or wear long, soft sleeves.

And allow me to pile on. Consider this, too: there is no Dorothy in Wicked. There is no little girl who with her dog Toto wakes up in the Land of Oz. In Wicked, that little girl is Elphaba.

A Sensational Supporting Cast

There is so much to be praised. Ariana Grande’s Glinda is everything and more that Kristin Chenoweth first brought to the stage version. A precocious little princess who is so self-adoring, our laughter is organic. Grande is a beautiful, fluid dancer whose comic timing is in step with her every gesture, and—who doesn’t already know it?—has a voice that hits notes way, way higher than any rainbow. Casting Grande in the role of the Good Witch is pure genius. And casting Jeff Goldblum as the Wizard is just as brilliant. He’s no bumbling fool, but his staccato cadence and body gestures make him a standout in this unbelievable world which he alone believes he owns. He’s Pittsburgh’s own perfect professor of perfidy. Other standouts are many. As Fiyero, Jonathan Bailey proves his dancing chops, sliding on books, and swinging from ladders that help make up a library set that’s just as amazing. Ethan Slater as munchkin Boq Woodsman is charming. And Michelle Yeoh gives added dimension to the character of Madame Morrible.

Nathan Crowley is the production designer who has recreated Oz in every fantastical detail. One must agree that bringing Wicked to film required marrying our shared (perhaps historic) vision of this land that is not Kansas with a more modern ideal of an Emerald City. Crowley does not disappoint. Shiz University is grand, its library as clever as the books it holds. The trip to Oz is by a stylized train which is neither steam-punk, nor Star Wars, but something that approximates every American boy’s favorite Erector set. Just as noteworthy in many ways are the hundreds of costumes in this very visual Wicked. Paul Tazewell’s work is evident from eye glasses down to glittering shoes, with a lot of color in between.

Used to be (is it still?) that friends recommended movies rated on the number of handkerchiefs one must bring. Ain’t nothing wrong with that. But the theater nerd in me always looks to understand the why—is it the situation, plot, conflict or character?—that inspires those tears. Wicked isn’t just a joy to behold, it’s got layers of character that reveal truth in a way that MGM first showed us 1939. A black & white world becomes filled with color. And a character to be pitied realizes that betrayal defies all understanding of what is good and what is truly wicked.

C. Prentiss Orr is a Pittsburgh-based writer who covers film, live theater, and other topics for Entertainment Central. He is the author of the books The Surveyor and the Silversmith and Pittsburgh Born, Pittsburgh Bred.

Share on Social Media

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter