Prince of Pop Meets Street-Art Phenom: ‘Warhol and Basquiat’ at The Warhol

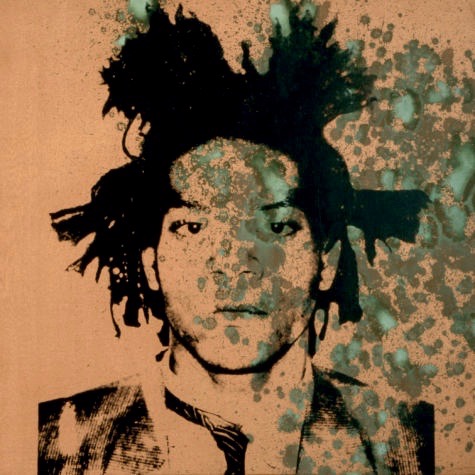

Looking at you, kid: Jean-Michel Basquiat, in a portrait by Andy Warhol, circa 1982. (Image © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts)

The largest piece in the show at The Andy Warhol Museum is the craziest. Blatantly symbolic and overstated, it maybe shouldn’t work at all. But luckily the museum supplies a bench in front of “Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper),” because I needed to sit a bit to digest its impact.

“Ten Punching Bags,” created by Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1985-86, consists of bright-white heavy bags—the long, cylindrical ones—hung in a row. Painted in black outline on each is a face of Jesus, appropriated by Warhol from Leonardo’s “Last Supper.” And each bag is marked up, brutally, by Basquiat. The gentle, benign faces show gashes and scars. Moreover, scrawled here and there across every bag is a one-word message that contradicts the “Judge not” lesson from the Sermon on the Mount: JUDGE JUDGE JUDGE JUDGE JUDGE …

I am not able to unsee this. May never be. I would suggest visiting The Warhol to view the entire installation the piece is part of, Warhol and Basquiat in Focus (through September 20). Pulled from items in the museum’s vast permanent collection, the show highlights Warhol’s late-life friendship and collaboration with a mercurial artist nearly 32 years younger.

Basquiat was closer in age and background to Keith Haring, a fellow New York graffiti artist who broke into the big time at the same time. However, Basquiat blazed his own path to being a living legend and, since his untimely death, a legend in retrospect. Posthumous movies about him range from the 1996 biopic Basquiat (with David Bowie playing Warhol) to the 2017 documentary Boom for Real. 2017 was also when one of Basquiat’s paintings set a new record for price paid at auction for a work by an American. His spooky, untitled 1982 rendering of a skull-like head fetched $110.5 million at Sotheby’s. Which triggered a new round of postmortem articles about the artist, and stirred up old debates about whether he was a true genius or a product and ultimately victim of art-world hype.

For readers who have missed the buzz, here is a whirlwind bio of Basquiat, followed by more about the show.

A Life in Fast-Forward, from Soup to Madonna

In 1960, while Andy Warhol was making his name in Manhattan, a baby was born in Brooklyn. Jean-Michel’s father, Gérard Basquiat, had immigrated from Haiti when young and had done well. He worked his way to an accounting degree and a nice profession while marrying a cultured woman of Puerto Rican descent, with whom he set out to raise an all-American, immigrant’s-dream family.

Young Jean-Michel was precocious, reading and writing early in his family’s three languages. He showed a passion for the arts which his mother, Matilde, encouraged. When Jean-Michel was eight, he endured a hospital stay after being struck by a car, so Matilde brought him what she thought was an ideal get-well gift for her clever lad: a copy of Gray’s Anatomy. The boy loved the book and years later would co-found a band called Gray.

But long before then, the family’s dream wagon careened off course. Mom and Dad split up. Matilde became a chronic inpatient, for psychiatric care. And to Gérard’s dismay, his oldest child and only son lost interest in formal education. Jean-Michel wound up at an alternative high school—the kind for promising but contrary teens—and didn’t finish. Reportedly his alternative activities had included pie-ing the principal. The kid from bourgeois Brooklyn was intent on taking his art, and his life, to Manhattan’s streets.

Basquiat first won wide notice as part of an anonymous graffiti duo. He and buddy Al Diaz tagged their work SAMO©, short for “same old shit (copyright).” Their graffiti used few if any graphic flourishes, often consisting just of cryptic text, like SAMO© AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO MASS-PRODUCED INDIVIDUALITY, or PAY FOR SOUP, BUILD A FORT, SET IT ON FIRE. In a 1978 interview in The Village Voice, Basquiat, then 17 and identified only as “Jean,” implied that this sort of thing was another pie in society’s eye: “They’re doing exactly what we thought they’d do … We tried to make it sound profound and they think it actually is! That’s like a heavy compliment, man.”

From there, Basquiat’s rise to international art stardom went insanely fast. He drew and painted on blank postcards, on clothing, on the walls and furniture of Lower East Side apartments where he crashed. Hawking his postcards in the street, he spotted Andy Warhol and sold him one—but that was merely a prelude to a friendship yet to come. Leveraging his SAMO© reputation, Basquiat made rapid forays into nearly every corner of the counterculture arts scene of the time. With Gray, an experimental noise band made up of non-musicians, he played venues such as CBGB and the Mudd Club. Along with Debbie Harry of Blondie, he co-starred in an indie film and made his first sale of a painting on canvas to Harry, who bought “Cadillac Moon” for $200. Meanwhile he’d entered a group art show in an abandoned Times Square massage parlor, where his paintings were noticed by critics. This led to a more upscale group show, and to art dealer Annina Nosei providing him workspace and materials in the basement of her gallery, where he painted rough-edged, bristling pieces like “Irony of Negro Policeman.”

Then he was off to the races. 1982: Basquiat, at 21, becomes the youngest artist invited to the prestigious documenta show in Kassel, Germany. 1983: at 22, he’s the youngest artist ever shown at the Whitney Biennial in New York. Basquiat’s style was seen as neo-expressionism, which in lay language might translate to “oozing with energy,” a description that fit Basquiat the person. A poetic article in Artforum had called him a new incarnation of “The Radiant Child.” He was charming and playful but seemed perpetually unsettled. He jet-setted and switched dealers, trailing a cavalcade of girlfriends that included, briefly, a young singer-dancer named Madonna Ciccone. He’d rake in money from his paintings, splurge it away and then paint to earn more.

Are You Working for The Man or WITH The Man?

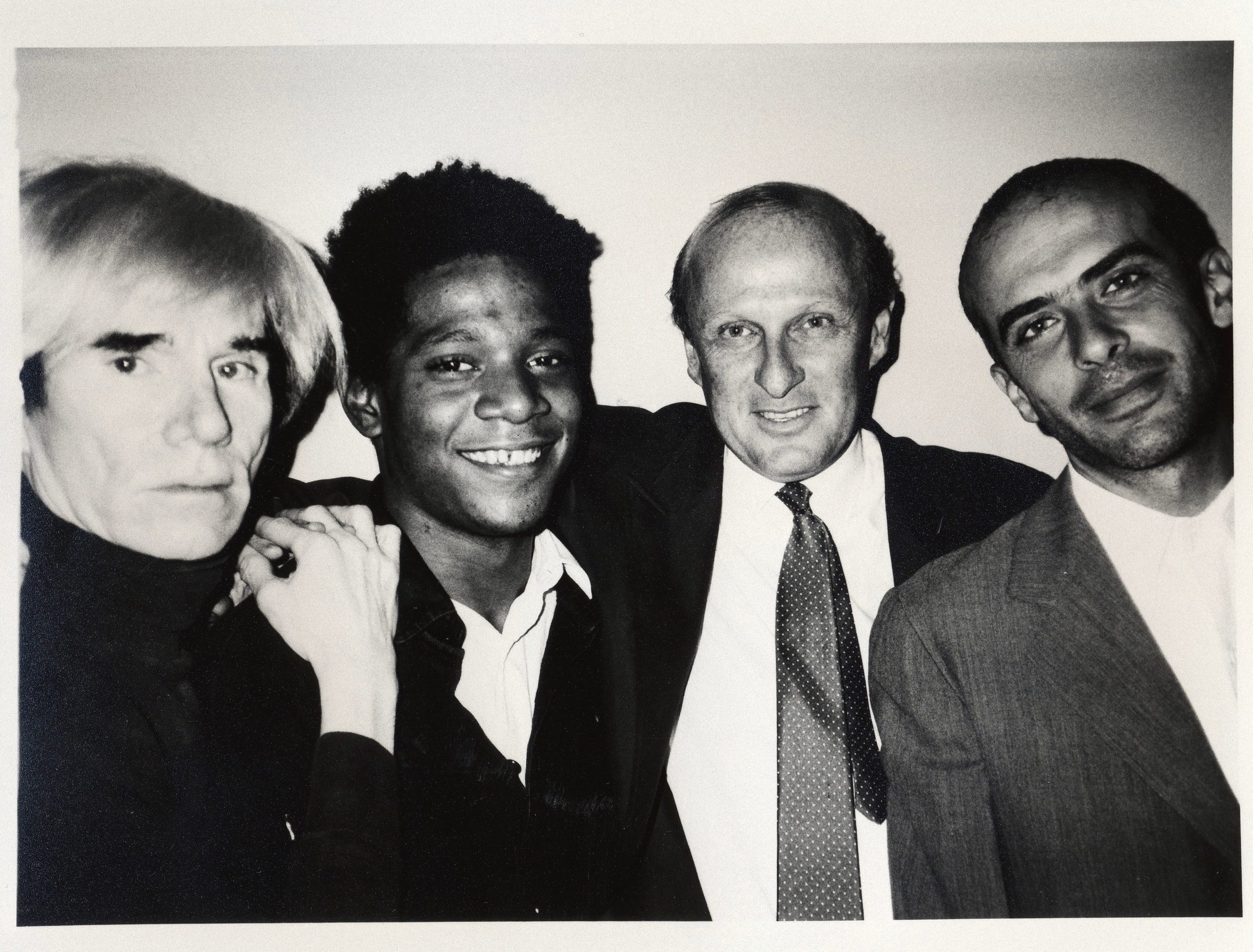

Warhol and Basquiat (L) teamed up with artist Francesco Clemente (R) through Bruno Bischofberger, the guy in the tie. (Photo, 1984, Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, shared via CC BY-SA 4.0)

Amid this rocket ride, the Swiss dealer Bruno Bischofberger introduced Basquiat to Warhol. The fascination was mutual. The young phenom and the 50-something silver fox started visiting frequently, usually at Warhol’s place. They worked out together, clowned around and went to dinner together, and eventually, at Bischofberger’s urging, they collaborated. Early joint work included the Italian painter Francesco Clemente; the dealer promptly sold a bundle of their 3-man pieces. After Clemente moved on, Basquiat + Warhol continued. Since both men worked fast, they produced a sizable body of collaborative art, of which Warhol and Basquiat in Focus offers a fine selection.

The museum’s Jessica Beck, who curated the show, wants to dispel the notion that Warhol became a mentor to the younger artist while Basquiat was the mentee. “They were friends. They were mentoring each other. The relationship was reciprocal, and there was a lot of creative energy between them,” Beck said in a phone interview. “When you look at the paintings, you start to see the influence Basquiat had on Warhol,” she said. “He had Warhol thinking expansively about painting.”

Other observers have noted this influence. In the years leading up to the collaboration, Warhol’s work had narrowed mostly to silk-screen portraits. The pieces he did with Basquiat reveal an opening-up of subject matter and a return, by Warhol, to painting by hand. Beck further pointed out that one can often see a “multidimensional” interplay in their work together: “There’s a back-and-forth of gestures,” which produces “a true harmony” that is dynamic and generative, not static.

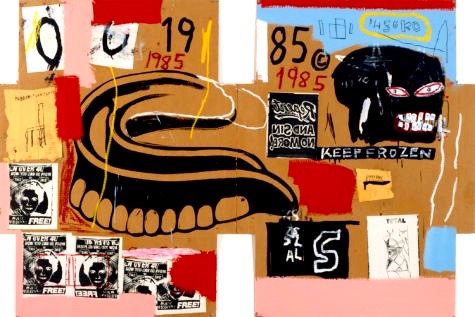

Maybe you never thought about teeth in quite those terms. But it has been said that we Americans think with our teeth—constantly nibbling, constantly grinding—and “Dentures/Keep Frozen” spins off thoughts ranging from comical to scary.

If the teeth fit, wear them. Or perhaps fear them. Basquiat and Warhol did “Dentures/Keep Frozen” on cardboard. The fierce, toothy head on the right is a signature Basquiat motif. (Image © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat)

Basquiat also inspired Warhol to “think politically and personally about painting,” according to Beck. Her text panels for the museum show provide plenty of context about socio-political issues that were prominent during the time the two artists worked together. Notably, and tragically, the HIV/AIDS epidemic began in the early 1980s. At first the virus was poorly understood and nearly all who were infected were gay men, leading many people to think the disease was a problem limited to—and even a judgment upon—the unfortunate men. (Beck believes the “JUDGE” messages in “Ten Punching Bags” could be an ironic comment on that view, although the piece clearly has broader implications as well.)

There’s no question that Basquiat got Warhol thinking about racism. In 1983, a Black graffiti artist named Michael Stewart was arrested while tagging in a New York subway station late at night. It seems the Transit Police handled him violently: students at nearby Parsons School of Design said they could hear him wailing from inside their dorm. Stewart was rushed from the local police station to a hospital, where he died in a coma. The police officers involved were later acquitted of negligent homicide. One piece in the Warhol and Basquiat show, an untitled collaboration, comments on the Stewart case. It’s a jumbled heap of twisted canvases and distressed faces.

However, the piece that spoke to me about race issues most profoundly is a simple painting. “Chairs/African” depicts two white wicker armchairs standing empty in a green field, while a grim black figure squats on the ground before them. Rarely does one see such a haunting message visualized so plainly.

The show does include some playful artworks, but these too have a bite. As someone who has dealt with rats, both the four-legged and human varieties, I found the large painting “Year of the Rat/Rodent™” triggering my rat radar. The piece conveys the essence of rat-ness. And as for “Dollar Sign, Don’t Tread on Me,” I would leave you to draw your own interpretations.

All the serpentine symbolism you need. Basquiat’s snake appears to be eating its own tail, which would reference the mythical Ouroboros. And Warhol’s fine sense of color helps “Dollar Sign, Don’t Tread on Me” sing. (Image , © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat)

Bitter Ends and Living Vibrations

The collaboration between Warhol and Basquiat had an unhappy end. In 1985, after about two years of co-creating, they presented an exhibition of their paintings at a New York gallery. The posters for the show, with the two guys posed in boxing gloves like sparring partners, were great. The opening-night party was great. Everything was uniformly great except the reviews. Critics panned the paintings as being “inconclusive” and “infused with banality.” One even questioned the men’s relationship, referring to Basquiat as Warhol’s “mascot.”

Apparently Basquiat was stung to the core. His visits to Warhol tailed off. He phoned maybe once in a while, or maybe not. Time ticked on. Warhol lamented his young friend’s absence but kept producing new work until 1987, when he died unexpectedly after gall bladder surgery. Basquiat didn’t last much longer. His ascent to the high life had always involved transactions with dealers other than art dealers. Friends (including Warhol) had been increasingly alarmed by the effects. More cocaine made Jean-Michel paranoid and more heroin made him deceased, in August of 1988, at the age of 27.

Yet there is a very real sense in which artists live on through their work. Until visiting Warhol and Basquiat in Focus, I had not been much of a Basquiat fan. I had seen his art only on the screen, or in reproductions in printed articles, and hadn’t felt an emotional connection with it. Absent this connection, art becomes merely academic, as in “Interesting, but so what?”

Seeing his work in the flesh, as it were, enabled me to connect. You can feel the guy’s energy. You can feel it vibrating with Warhol’s. I recommend the experience.

Closing Credits and Visitor Information

Warhol and Basquiat in Focus, curated by Jessica Beck, runs at The Andy Warhol Museum through Monday, September 20. Beck is the Milton Fine Curator of Art at The Warhol. The museum is open Wednesdays through Mondays; closed on Tuesdays. At the time of this writing, advance timed reservations were still necessary in order to visit. See the museum’s Admission & Hours page on the web for more details. 117 Sandusky St., North Side.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer, covers visual arts for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter