CLO’s ‘Musical Christmas Carol’ Features the Miser, the Mirth, and the Mythical

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

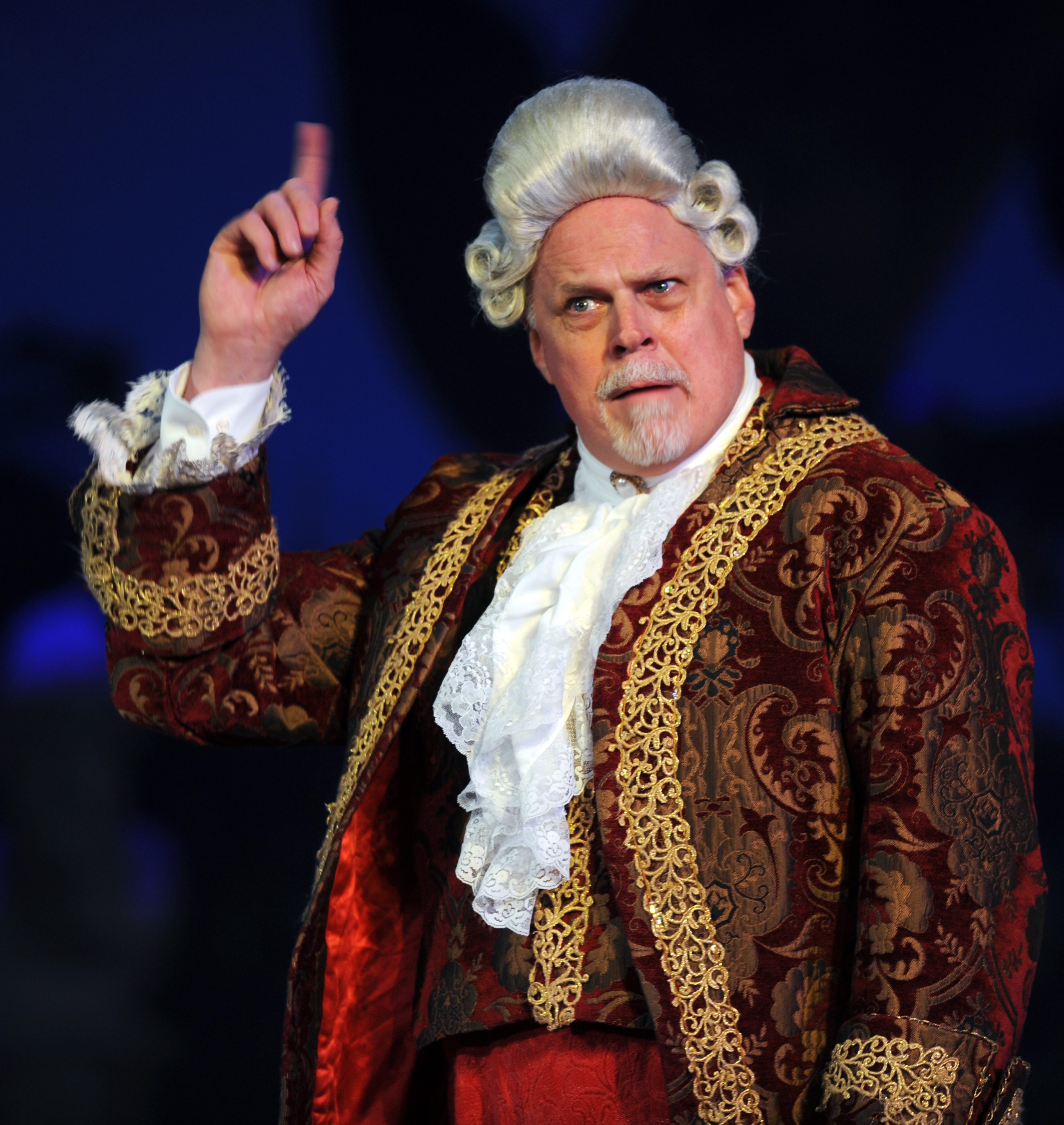

Scrooge (Patrick Page) sees the fires of Hell a-burnin’ and begs for a re-do. If the feeling hits home, that’s one reason the story lives on; Pittsburgh CLO’s adaptation adds new twists to the Dickens original.

The year is 1843. Charles Dickens is hard at work on the novel that he’s sure will be a masterpiece, securing his place in the pantheon of great writers. It is a big, sprawling, satirical saga called Martin Chuzzlewit. If you can find a copy on a library shelf, it may have cobwebs attached.

Amid the labor and worry over Chuzzlewit, Dickens took a few weeks to pen a little book just in time for the Christmas of ’43. You know the name of that one. For Pete’s sake, everybody knows it, even in Japan, where Kurisumasu Kyaroru (the Japanese pronunciation) is, according to one scholar, considered “one of the most famous works of English literature, possibly in the same league with Hamlet.”

Even people who’ve never actually read Dickens’ A Christmas Carol know the story, from countless adaptations in every medium invented thus far. Surely more people have seen Ebenezer Scrooge than the Danish prince.

Pittsburgh CLO is presenting its favorite stage version, titled A Musical Christmas Carol, through Dec. 23. And wonder of wonders, despite the availability of many other versions on home TV, good seats at the Byham Theater are going fast—to parents with children, to couples without children, to patrons of every demographic cohort from pre-Boomer to post-Millennial.

Do people have money to burn or what? More likely, the crowds are drawn by the power of the live performance and the undying appeal of the story itself.

Out of the Mist, a Compelling Myth

This is supposed to be a review of the CLO play. We cannot indulge in lengthy commentary on the amazing phenomenon that the story itself has become—although your friendly reviewer is tempted to—so a few notes will have to suffice.

The story is literally incredible, that is, it defies belief. Miserly, misanthropic meanies don’t change into loving benefactors overnight, not even in the unlikely case of being visited by spirits that show them the profound error of their ways. No therapist worth his/her third-party reimbursement would expect it. And yet despite such hocus-pocus, wrapped in sentimentality thicker than the London fog, Scrooge’s story does what every good story does: it rings true to human experience. It strikes a universal chord.

Try watching (or reading) it without tears coming to your eyes. Go on, we’re waiting. You had to hold them back, didn’t you?

Why, it’s Bob Cratchit (Jeffrey Howell) with Tiny Tim (Marco Attilio Petrucci)! Looking on in the background, the Ghost of Christmas Present (Tim Hartman) sees a grim fate in store unless a certain you-know-who repents.

Nor is the Scrooge story merely a cheap weeper with a happy ending for the pop-culture masses. A Christmas Carol has legions of admirers in the highest artistic circles. Illustrious actors who’ve eagerly played Scrooge range from Lionel Barrymore (in voice only, on radio) to Marcel Marceau (in mime, with no words).

And according to some critics, the story has attained a rare cultural status. It has become a myth—a legend or fable that says something fundamental about us. That’s why we keep coming back to it. And why there are so many adaptations, every Christmas, everywhere… including A Musical Christmas Carol.

Fleshing out the Bones, Puttin’ in the Jazz

One word: party! Fezziwig (Tim Hartman) runs a tight ship but he bursts loose at Christmastime.

Pittsburgh CLO is using a script by American writer/director David H. Bell. He is best known for Hot Mikado, the jazzed-up remake of Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera The Mikado, but you won’t find any bebop in Bell’s adaptation of A Christmas Carol. Indeed, there is not much music at all. Although the cast breaks out into some high-spirited hoofin’ at Mr. and Mrs. Fezziwig’s Christmas party—a party that Scrooge revisits with the Ghost of Christmas Past—that brief romp is the only true song-and-dance number in the show.

Members of the ensemble sing lines from “Silent Night” and other traditional Christmas songs as preludes to scenes or as bridges in the action, and that’s about it music-wise. A Musical Christmas Carol is really a “play with music,” not a musical.

Bell has, however, jazzed up the content of the story. Dickens’s original was done in a rush and the writing is often described as uneven. Some parts are marvelously rendered, with snappy dialogue and vivid imagery. (When Scrooge goes home to his apartment late at night and sees Jacob Marley’s face in the door-knocker, the apparition has “a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar”—and that’s just the start of a surreally hair-raising scene.) But other parts are barely roughed in, summarizing major plot shifts with a few vague sentences.

Dickens might have given those parts a much fuller treatment if he’d had time, and Bell’s stage adaptation takes the time. One sequence that has been added does a great job of conveying young Scrooge’s transition from a hopeful, even idealistic teenager to a cramped money-grabber. At Fezziwig’s Christmas party, the youthful Scrooge—then a hard-working apprentice—is pulled aside by a guest who turns out to be Marley, his future partner. Marley offers the kid a chance to make a lot more money faster. And there’s a catch. The move will require the kid to betray Fezziwig, a master he loves.

Naturally, young Scrooge (played with quiet brilliance by Luke Halferty) hesitates. But gee, as a guy engaged to be married, he sure could use the boost, so he goes ahead. Follow-up scenes show the unhappy consequences for the Fezziwigs, for Scrooge’s fiancée, and ultimately for Scrooge himself. Most of this is not in Dickens’s novella, but it’s some of the most powerful stuff in A Musical Christmas Carol.

Marley’s ghost (Daniel Krell) is too weird for words—yet he speaks.

Hoots and Oddities

Comic scenes are added, too. The elderly Scrooge’s housemaid gets some choice moments on stage, and she is a hoot. Terry Wickline shines in that role as well as the ribald Mrs. Fezziwig, where she’s paired with Tim Hartman, who plays the Mr. with suitably rooster-like ebullience.

All the actors are spot-on for their roles. As the adult Scrooge, CLO has Patrick Page, known nationally for playing stage villains. Page is nasty enough in the early going, but the big surprise comes after his transformation, when he sports a billion-dollar smile that lights up the house.

Unusual touches include Marley’s ghost (Daniel Krell)—made up and portrayed in such a gruesomely over-the-top manner that the scene almost comes across as parody, though it certainly is memorable—and the Ghost of Christmas Present. Often this spirit is played as a right jolly big fellow who, at key moments, turns serious to deliver pointed barbs to Scrooge. CLO’s Christmas Present (Hartman again) is sterner throughout, more like an avenging angel crowned in holly.

The Elephant and the Verdict

Which brings us to the elephant in the room. It is a question that comes with every adaptation or reading of A Christmas Carol, and it looms large in today’s politically charged times. Is the story a critique of capitalism?

There are lines and scenes that support the view. In one of the many exchanges in the CLO play taken directly from Dickens’ original, Scrooge tries to comfort Marley’s mournful ghost by saying: “But you were always a good man of business, Jacob.” To which Marley replies: “Business?! Mankind was my business! The common welfare was my business …” and so forth.

Then again, many have argued that Dickens’ story is by no means an attack on free enterprise or the industrial order; that it’s a screed against greed but not against the prevailing economic system. I will leave the elephant to you, dear readers. The pertinent question for this review is one regarding the artistic quality of CLO’s A Musical Christmas Carol: How well does it work?

I’ve seen way too many adaptations to judge clearly, so, as the show ended, I turned to the couple next to me. The man flashed a double thumbs-up. Then he and his partner joined the majority of the audience in a standing O.

Closing Credits and Ticket Info

Pittsburgh CLO’s executive producer for A Musical Christmas Carol is Van Kaplan. The production follows direction and choreography by David H. Bell, the writer of the adaptation, with musical direction by McCrae Hardy. This is the 25th anniversary showing of the play at CLO, featuring 24 actors and singers on a new set designed by D Martyn Bookwalter.

Through Dec. 23 at the Byham Theater, 101 6th St., Cultural District. For showtimes and tickets visit CLO on the web or call 412-456-6666.

All photos are by Matt Polk.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer and editor, covers theater for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Follow Entertainment Central

Sign up for the EC Newsletter

Latest Stories