‘Bridge of Spies’ Is Powerful, But Heavy on the Schmaltz

It seems odd to say this but the new historical thriller, Bridge of Spies, succeeds both because of and in spite of its director, Steven Spielberg

As he’s proved time and again, there’s not a more technically proficient movie director than Spielberg. His singular ability to tell a story using the pure mechanics of film was evident with his first big hit, Jaws in 1975, through the various Indiana Jones and Jurassic CGI extravaganzas. Our good friend Steve certainly knows how to put a movie across.

At the same time, Spielberg has a great deal of trouble controlling his addiction to cheap, manipulative sentiment. From E.T. and The Color Purple with stops along the way for Saving Private Ryan and War Horse, among others, he just can’t help tugging at your heart-strings … if not tying them up into quaint little bows.

None of that, by the way, is a necessarily a complaint. It is what it is and you know all of it going into a Spielberg film—it’s his thing.

He runs into trouble when he inserts the mawkish, calculated emotionalism of his special effects movies into the historical films he’s favored in later years. Amistad (the 1997 retelling of a slave revolt) was confounded by his need for a feel-good ending. The taut story about the fallout from the 1972 Olympic massacre, Munich, got bogged down by his need to make us feel for the film’s characters. And as brilliant as the 2012 biopic Lincoln was, it was marred by the attention he brought to bear on some of the soap-operatic elements in Lincoln’s life.

Which is not to say that there weren’t some positive outcomes to the Amistad rebellion, or that the Mossad assassins (and Palestinian terrorists) didn’t suffer from human frailty, or that Honest Abe’s home life wasn’t a messy business. The problem is that Spielberg will not allow us to discover any of it for ourselves. He’s a deft hand at lacing these elements throughout his films … and then banging them over our heads (usually with a John Williams string crescendo) to make sure they hit home.

Steve, we get it already.

Bridge of Spies is a case in point. This film, from a sleek screenplay by Matt Charman and Joel and Ethan Coen, based on real-life events, illuminates a nearly forgotten episode in our country’s past.

The True Story

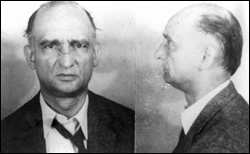

In 1957 Rudolf Abel, a Russian spy living in Brooklyn Heights, was arrested and tried in federal court. The U.S. government, anxious to make sure it looked to the world like Abel was receiving a fair trail, hired James Donovan, a private lawyer who had worked on the Nuremberg prosecutions, to represent the spy.

In truth, nobody (not the government, court officials, nor the American public) really wanted Abel to be found innocent. And while Donovan didn’t achieve that verdict, he did make sure Abel received the most equitable trial he could—or at least as an accused Russian spy during the Cold War could. Donovan also managed to have Abel spared from the electric chair and given a long prison sentence.

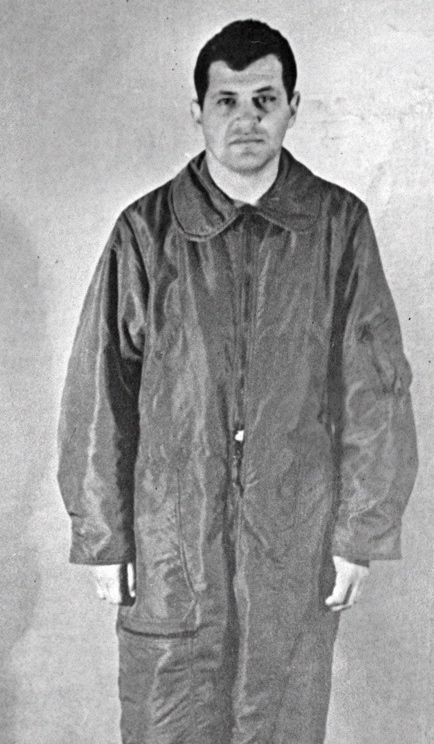

Jump ahead to 1960: Francis Gary Powers, an Air Force pilot, is shot down over the Soviet Union in a CIA spy plane. This caused some trouble, since the U.S. government had been insisting that America would not violate Soviet air space to spy from the sky—and now Powers was captured alive, along with items from the wrecked plane which clearly showed what he’d been up to.

Oops.

Donovan, in an officially “unofficial” way, was pressed back into service to arrange a spy swap: Abel for Powers (and an American student, Frederic Pryor, who had been taken prisoner by the Stasi in East Berlin.)

The Movie’s Many Strengths

Spielberg gets so much of it right. There are several edge-of-your-seat sequences, expertly filmed and tightly edited. The performances by Tom Hanks as Donovan and Mark Rylance as Abel are controlled and detailed, and the two men have a wonderfully unique ability to convey so much with charged silences. Spielberg has, in fact, assembled a knockout cast who bring a huge amount of ability to the project.

Spielberg also does a great job of providing the context against which the events played out. He captures the Cold War hysteria and the hyper-masculine culture of the time, which invariably led to an us-against-them mentality and the Politburo-like mindsets of both the Soviet Union and the equally ideological U.S. intelligence agencies.

One of the more fascinating aspects of the film is the vivid portrait it paints of an America now all but forgotten. Some may not remember that the global organizing principle of much of the 20th century was not only the Cold War but also the various proxy wars between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, played out around the world for nearly 80 years. Politically, socially, and culturally, America defined itself as the moral antithesis and sworn enemy of Russia. All decisions made in foreign policy, and a lot of the domestic ones, were based on our righteous opposition to the dirty Reds. Bridge of Spies does a terrific job of evoking what that was like.

What’s most amazing for the modern viewer is to realize that barely 25 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, it’s as if none of it ever happened. Billions of dollars were spent, millions of lives ruined, and our own national identity warped—and yet now it’s like a bump in the road seen in a rear-view mirror. I’m sure most young Americans with no grounding in history (which, sadly, might be most) will watch Bridge of Spies and be surprised to see everyone looking so jumpy.

Aw, Come On, Steve

Which brings up the typical Spielbergian flaw. Steve can’t leave well enough alone. He’s going to forge an emotional connection between the audience and the film if it kills him! (And wearies us.) Spielberg continually lards the movie with scenes of emotional manipulation, usually involving little children with big eyes crying because they’re afraid of the H-bomb, or older children in tears because of mob rule run amok … or sometimes what he does is just needless pandering.

There’s a particularly egregious occurrence near the end of the film. I can’t reveal it but it involves—you guessed it!—children playing in a back yard. Right before this shot, Spielberg has created a beautiful sequence recalling an earlier scene in the film. You sit there thinking how quietly, and disquietingly, evocative it is … and then here comes Spielberg, the Corn King, to drag out those damned kids and clobber you on the head.

It’s moments like this which bloat the film and make you feel every one of its 141 minutes. But ultimately, Spielberg is saved by his own knowledge of the craft, by powerful performances, and by an intelligent script that tells a compelling story. So you should definitely catch Bridge of Spies, but here’s a viewing tip. Whenever a kid shows up on the screen, use that time to get your popcorn bucket refilled.

The real “Bridge of Spies”: During the Cold War, the Glienicke Bridge in divided Germany was a no-walk zone, as Western forces controlled one end and Communist forces the other. But the bridge was used for exchanging captured spies and it’s where the U.S. swapped Rudolf Abel for Powers.

Photo credits: Rudolf Abel, FBI. Francis Gary Powers, Russian International News Agency (RIA Novosti) via Creative Commons ShareAlike license 3.0. Glienicke Bridge, by Manfred Brückels, also via CC SA license 3.0.

Ted Hoover is a Pittsburgh-based writer and critic.

Share on Social Media

Follow Entertainment Central

Latest Stories

Sign up for the EC Newsletter