Art at the 58th Carnegie International: Seeking a Greater Good

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Videos at the Carnegie International aim to push the envelope. This scene from Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s ‘Lugar de Consuelo’ (‘Place of Solace’) may not fit everyone’s idea of a sanctuary for healing.

A certain kind of cultural product is not so much a must-see as an automatic see. You go to see it because it is there, and it’s considered important. Some people would put Elton John’s last concert tour in this category. For many art lovers, and even for many who are merely infatuated, the Carnegie International is an automatic see.

The Pittsburgh event is one of the oldest and largest recurring shows of contemporary art from around the world, dating from 1896. Lately it happens only once every four years, and the current edition—the 58th Carnegie International, on view through April 2 at Carnegie Museum of Art—offers reasons for visiting other than highbrow FOMO. The art is good. There are pieces that stir the heart and move the mind. Moreover, the exhibition as a whole is a groundbreaker. It differs from previous Internationals in a couple of eye-opening ways.

Whereas Internationals in the past stayed literally contemporary, focused on living artists, the 58th includes a lot of modern but not-so-recent work from artists who have left us. You’ll see sculptures done in midlife by Kate Millett (1934 – 2017). Paintings by the Balinese artist known as Murni (1966 – 2006). And items that are more historical artifacts than visual art, such as manifestos written by artists and intellectuals in literary magazines from the 1930s to the 1950s.

There’s a reason. The show traces patterns of human development through modern times— often with an emphasis on patterns of arrested development. Kate Millett was the author of Sexual Politics, and her sculptural assemblies depict women imprisoned by symbolic barriers. (A vivid one is a woman’s head served up, as if on a platter, within a circular cage.) Many pieces depict or refer to wars: World War II, the Vietnam War, revolutions and counter-revolutions in Central America, wars in the Middle East. Most of the manifestos are from countries that were possessions or puppet states of foreign powers at the time. More than any International that this reviewer has seen, and I’m old enough to have seen plenty, the 58th is steeped in social commentary and socio-political awareness.

Mohammed Sami, an Iraqi artist living in exile, paints striking images that engulf the eye. “The Fountain I” is a towering inferno seven feet high.

A grim show? In a number of cases, yes, but it’s beautiful. Among the abstract works are large murals by the Vietnamese painter Thu Van Tranh. I spent some time mesmerized by the interplay of ghostly colors and shapes. Only after reading the text panel did I learn that the “Colors of Grey” series refers to the long-term effects of herbicides like Agent Orange that were dumped on Vietnam by the U.S. military.

Are You Woke Yet?

Recent Internationals have had thematic statements. The theme of this year’s is, “Is it morning for you yet?” Promo material explains that the question is an English translation of a traditional greeting used by the Mayan Kaqchikel people. The question is more poetic and personal than a bland “How are you?” It recognizes that a bright new day is here, but that everyone may not be experiencing it, and one can see how it might apply to social inequality. Also, whether the allusion is intentional or not, “Is it morning for you yet?” could conceivably be taken to mean “Are you woke yet?”

The word is used mostly as a pejorative these days, rarely spoken by folks who are actually woke. Some conservative-minded persons might write off the 58th International as ‘way too woke to bother with. I would suggest visiting anyway—for the quality of the art, and for experiences that should resonate with anyone regardless of their politics.

In an email interview for Entertainment Central, I asked Associate Curator Ryan Inouye about the political nature of the 58th International. He replied that an artist chosen for the show had asked the same, and that Chief Curator Sohrab Mohebbi had told the man that “no specific agenda or position was being advanced in the show other than opposition to ‘war, destruction, imperialism, and intervention … We believe in a possibility of peace.’” Inouye continued by saying “In this regard, we think Is it morning for you yet is about recognition of humanity and exploring ever-widening and more nuanced horizons for humanity on a global scale.”

Sohrab Mohebbi. (photo: Sean Eaton)

The catalog book for the exhibition includes a long essay by the chief curator. Mohebbi, an emerging star on the global art scene, essentially took a two-year leave from his post at New York City’s Sculpture Center to head the team for the International. He started in March of 2020, just as the Covid pandemic began, and writes that the eerie periods of isolation in lockdown helped to shape his thinking about the exhibition: “When the habitual collapses, we question the reason and value of what we have been doing, and why we have been doing it that way: Can we do it differently? Can we do it better? Should we give it up altogether?”

For Mohebbi, asking questions like these is not just armchair speculation. The curator is from Iran. He was a child in Tehran during the horrific Iraq-Iran War of 1980-88. And in 2020, amid the strange state of suspended animation that early lockdowns created, “I couldn’t help thinking of prior moments of unprogrammed time when living was also suspended,” he writes. “We would gather in the basement while a family friend played music as bombs were dropped on our city. It felt like making life out of nothing.”

Lights Out

“Ruins of Two Cities, Mosul and Aleppo,” by Dia al-Azzawi.

Sometimes, something can be turned into acres of nothing. “Ruins of Two Cities: Mosul and Aleppo,” by the Iraqi artist Dia al-Azzawi, draws its basis from the devastation caused by civil wars in those historic places. The close-up photo above doesn’t do justice to the piece. You must see it in person. The thing is vast. It covers nearly the entire floor space of one of the Heinz Galleries—I paced off the piece’s perimeter as measuring roughly nine yards by 12 yards—and its sprawling panorama is mind-bogglingly repetitive: rubble rubble rubble. If you’ve ever had a window seat in an airliner while descending to land near a big city at night, perhaps you looked down and marveled at the millions of lights twinkling everywhere. “Ruins of Two Cities” evokes the opposite sensation. This is how it looks in brutal daylight after the lights are bombed out.

The Car, She Is Us

Profile view of “car-body-screen,” a part of Tishan Hsu’s multi-piece outdoor installation, during initial setup for the International.

Some artworks are engagingly weird. One, viewable from the street, is installed on the Forbes Avenue plaza in front of the museum. Fans of old TV shows will recall a fantasy sitcom from the 1960s called “My Mother the Car.” We have come a long way since then. We expect our cars to be sentient creatures, and Tishan Hsu’s installation carries the vision far beyond the concept cars you may find at auto shows. The artist’s bulbous wheeled objects look like a metamorphosis of machinery into living tissue, or perhaps the other way around. Like what we would get if Kafka’s Gregor Samsa awoke one morning to find himself transformed into an automobile.

About Sex

Kate Millett, the sculptor of caged women, referred to sex as “the greatest cage of all.” The International offers a counterpoint to that view: florid, surreal paintings by I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih, a.k.a. Murni. Before her tragic death from cancer at age 40, the ebullient Balinese woman rocked Southeast Asian galleries and shocked her homeland with art that put her sexuality front and center. As well as in other imaginative configurations.

Murni’s “Berdadan” (“Dressing Up”) is one of her tamer paintings.

Twenty-three of Murni’s paintings are displayed at the International in a spectacular array. They include phallic imagery, vaginal imagery, sinuous bodies sprouting animal parts to show their animal nature (or, in one picture, a menacing pair of scissors sprouting from a woman’s groin), ancient Egyptian motifs, and more. The paintings convey both power and emotional complexity.

A woman I know once told me, “You can’t talk about sex. Because if you try to talk about sex, you have to talk about everything.” The point is that so much is wrapped up in it—and, one gets into things that language can only approximate. I am reminded of another woman I saw, years ago, at a poetry event. She mounted the stage to read her poems and began with a statement: “All of this is in code. The real words take longer.” Murni’s paintings speak in a code without words.

Other Highlights

The 58th International is a mammoth show. Artworks fill almost every available space in Carnegie Museum of Art. If you’re going, go more than once instead of trying to see the world in a day. A few personal favorites:

“La Libertad” (Liberty), a sculptural assembly by Margarita Azurdia, oozes irony in brilliant colors. A triumphant, carnival-like figure celebrates while sitting astride what appears to be a bull. But the bull stands on a platform festooned with human skulls. The symbolism is blatant but it’s very well done. Meanwhile, some photographs taken in conflict zones during the 1970s strike a subtly insidious note. “Extra-curricular Political Science Class,” by Võ An Khánh, shows a cadre of Vietnamese revolutionaries wearing spooky white masks to hide their identities. Across from this picture are Susan Meiselas’s photos of Salvadoran rebels, also masked—except they are wearing traditional masks of the region, which have facial expressions that are innocently charming, not warlike.

Many paintings aside from Murni’s caught my eye, and one titled “The Statue,” by Mohammed Sami, stays in my mind’s eye. It is simple and haunting: a view down into the bare corner of an open-roofed chamber, with the blurry shadow of a solitary person cast on one wall.

Zahia Rahmani’s “Seismography of Struggle,” shown here in a previous setting at INHA (France’s National Institute for the History of Art) in Paris.

Equally fascinating and, in a sense, equally haunting are the manifestos mentioned earlier. They can be read in an installation area that carries the hefty title “A Seismography of Struggle: Toward a Global History of Critical and Cultural Journals.” Art historian Zahia Rahmani put together the installation, which features wall projections of covers of journals plus one screen displaying excerpts of writing within them.

A long series of these excerpts appear one by one. Together they provide a sort of episodic, quick-take history of striving and aspiration. For example …

A declaration of intent from La revue des jeunes de Madagascar (The Journal of Young Madagascar): “The magazine not only seeks to instruct and educate its readers, it also aims at enhancing Madagascar in the eyes of other nations, not only for its agricultural, mining and industrial production but especially for its inherent qualities, the sum of its moral and intellectual powers.” That was written in 1935. Today—four score and seven years later—the former French colony is now an independent country but still struggles to gain the status envisioned long ago.

One sentence from Community, published in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) in 1954, delivers a perfect radical answer to critics calling for editorial balance: “No viewpoint will be excluded—but there is no obligation on the part of the editor to write up the convictions of people who are free to write for themselves.”

And from Khorous e-jangi (Fighting Rooster), published in Iran in 1951, we get a 15-point philosophical manifesto, of which the last point is “Death to idiots!”

Last Words

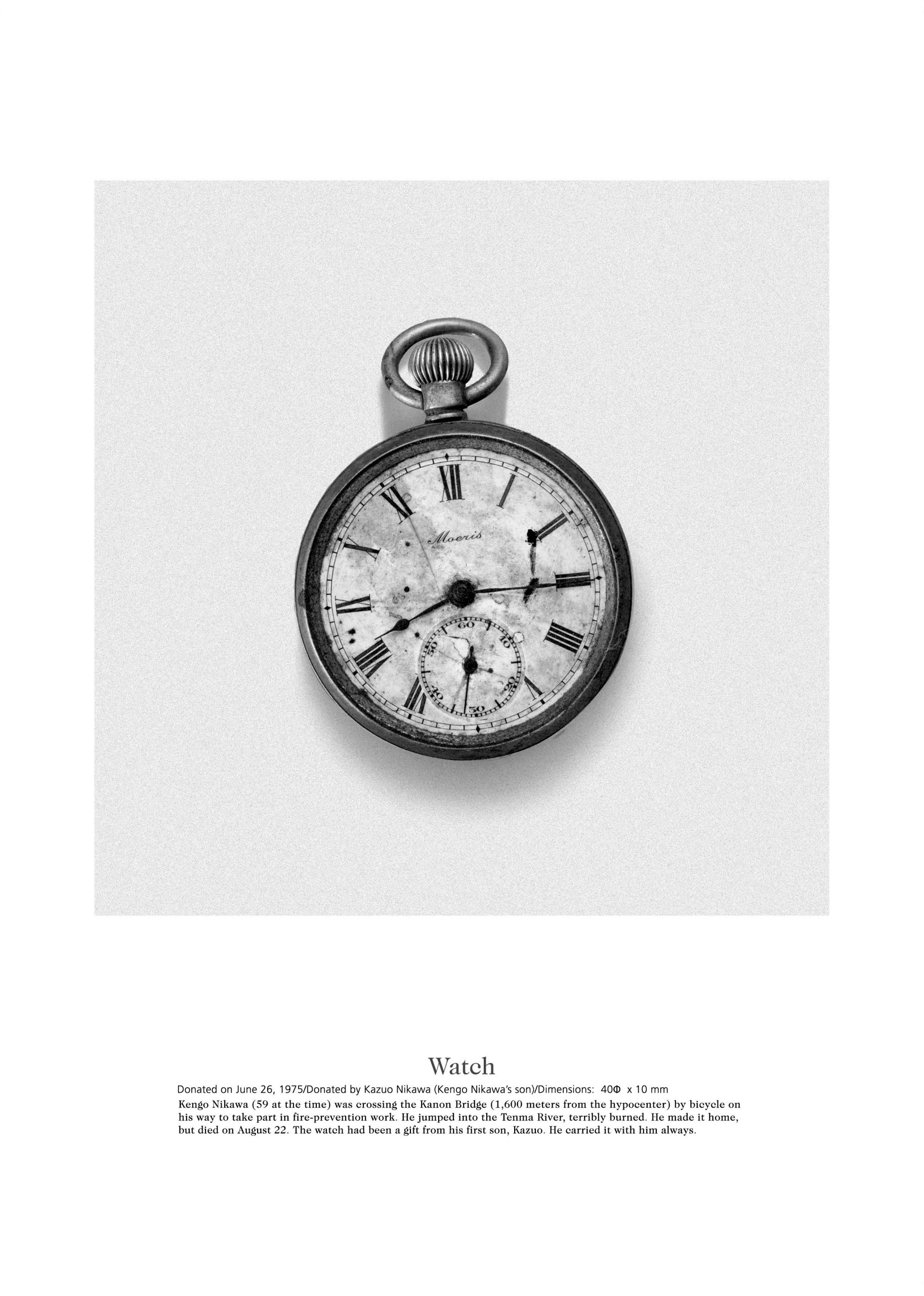

The problem with “death to idiots” is that hostility tends to kill many non-idiots in the process. Posted along the walls of the museum’s Hall of Sculpture are photos from Hiromi Tsuchida’s Hiroshima Collection. They are pictures of personal items gathered from the aftermath of the nuclear bombing of the city in World War II: a charred, half-burnt-away school uniform that a girl had been wearing. Battered lunch boxes and briefcases. A partially melted statue of the Buddha.

The items themselves are kept in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. In an interview for the 58th International catalog, artist Tsuchida noted the ongoing debates over the bombing, which revolve around whether the U.S. or the Japanese government was most to blame for the horrors inflicted. Then he said, “It will not be possible to divide participants in a future nuclear war into perpetrators and victims. It will be a global war in which all can be victims. I hope my Hiroshima series will make viewers feel such awareness.”

“Watch,” by photographer Hiromi Tsuchida. The atom bomb fell on Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. local time. A man’s pocket watch was stopped at that moment. The man did not survive.

Visitor Info and Exhibition Credits

The 58th Carnegie International runs through April 2, 2023 at Carnegie Museum of Art, 4400 Forbes Avenue in Pittsburgh’s Oakland district. Some works are installed at other locations around the city, and numerous special events and performances are part of the International. For complete information and tickets, visit the museum’s website for the show. Please note two key factors that may affect your planning: the museum is closed on Tuesdays, not Mondays as in the past. And you must reserve timed entry tickets online in advance of your arrival.

Organizing the International was a huge task, done by a team engaged for the purpose. Sohrab Mohebbi led the effort as the Kathe and Jim Patrinos Curator, with Ryan Inouye as associate curator and Talia Heiman the curatorial assistant. Since travel was restricted at times by the pandemic, the three relied more than usual on a global network of art experts and advisors for help in lining up artists and building the show.

Funding for the 58th International came from a multitude of sources in the Pittsburgh region and worldwide. A number of works in the show were commissioned, which means you will be among the first to see them—and which helps the artists to pay their bills!

Images of artworks were provided by Carnegie Museum of Art. The one exterior art photo is by the reviewer.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer, covers visual and performing arts for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Follow Entertainment Central

Sign up for the EC Newsletter

Latest Stories