The Public’s ‘Indecent’ Is More than Decent. It’s Extraordinary

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

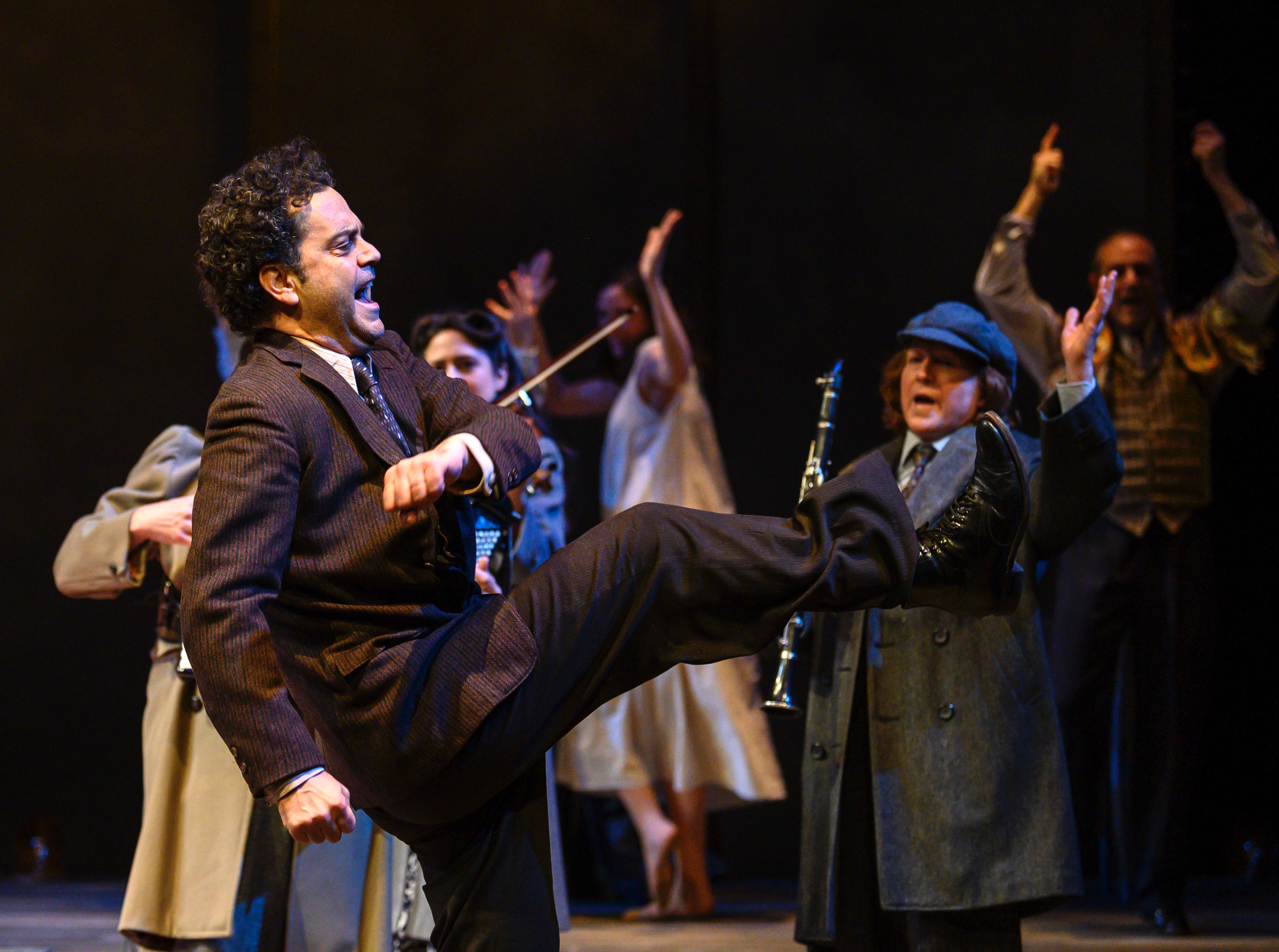

Few serious plays boogie to the extent that ‘Indecent’ does. Here, old Otto (Robert Zukerman) shows the young folks how.

Fellow theater fans, and fellow Pittsburghers, period: Have we got a play for you. It’s a complex play with unusual subject matter, maybe not the kind that you think would appeal to nearly everyone. But I dare anyone to see it and not be moved. You’ll laugh. You’ll either cry, or fight back the tears. You will come away from Paula Vogel’s Indecent, at Pittsburgh Public Theater, knowing you’ve had a rare experience.

Indecent (through May 19) transcends labels. One could accurately call it a history play, or a Jewish play, or an LGBTQ play. Or a play with music (lots of music), or a play about theater itself. What’s remarkable is how Indecent bundles these genres into a single package that’s a knockout.

The song-and-dance numbers would shine in a Broadway musical. There are passionate orations and nuanced, twisty-turny debates that feel like a courtroom drama. There are goofy scenes and ghastly, serious scenes.

A while ago I stopped judging the impact of plays by whether they got a standing ovation at the end. We live in an age of standing-ovation inflation, when even a turkey of a show can score a standing O. Many times I’ve watched audience members rise haltingly, as if calculating that it’s better to be polite than honest. But seldom have I felt a crowd rocketed up out of their seats in emphatic unison, as they were on opening night at Indecent.

The True Story Behind the Story

Indecent is based in fact. Although it includes made-up dialogue, and invents or alters a number of sequences for dramatic purposes, the major events depicted on stage really happened. They began in 1906 in Poland. A young writer named Sholem Asch, popular among the country’s Jewish readers for his stories in Yiddish, wrote a play that raised a storm as soon he showed the script to friends.

Titled God of Vengeance, Asch’s play was set in a Jewish brothel. The chief characters were the whoremaster, his daughter, and one of the working women. The plot: Papa’s been saving the money his employees have earned for him. He plans to see daughter Rifkele married off to a nice boy, but meanwhile, a lesbian love affair blooms—between Rifkele and the working woman. Imagine Papa’s fury when he finds out.

The tale had pathos and irony. A man who has prospered corruptly, from monetizing the act of love, is derailed by true love—in a form he cannot accept. Asch’s fellow Jews in Poland wouldn’t produce the play. They found it decadent, and feared it would inflame the anti-Semitism of the time by portraying Jews as low-lifes.

So Asch took God of Vengeance to a more cosmopolitan place: Berlin. Jewish theater artists there staged it, after which the play went to cities throughout Europe, drawing reactions that ranged from wild acclaim to “Immoral, indecent, garbage!” The controversy peaked in New York in 1923. An impresario had the Yiddish script translated to English, aiming to reach a wider audience. This set off alarm bells.

The entire cast was busted for obscenity. There would be no more God of Vengeance on 42nd Street. But it wasn’t the end of Asch’s play, nor is it the end of Indecent.

Lemml (Maury Ginsberg) provides the kickoff.

Into the Labyrinth

Indecent opens with a bang. Emerging front and center is Lemml (acted powerfully by Maury Ginsberg), who says he’s the “stage manager” for God of Vengeance. He introduces the rest of the cast amid wisecracks and song, while a trio plays rousing klezmer music. This opening clearly conveys that we’re going to see a play about another play, and it’s a great way to say “Welcome to metatheater.”

Then the story begins. And I must admit that through the first couple of scenes, I had misgivings. We meet young Sholem Asch (Robert Tendy) and his wife Madje (Emily Daly), who lovingly tells him that his new play is a work of inspired genius. Next we’re off to a formal reading, where writers older than Asch are disgusted by the script and tell him it’s no-goodski.

These scenes mix exposition with the action, as early scenes in a play usually do. To me the mixture felt forced and somewhat hokey. I worried that Indecent would be marred by the problem I’ve seen in some other plays based on true events. In straining to build a story around the facts, they come across as cluttered melodrama.

Not to worry. The play moves to Berlin with an exuberant—and hilariously naughty—song and dance in a nightclub. It’s another great musical bit. Instantly, the stiff-necked tension from the reading scene goes whoosh. You can tell right away that Berlin will be receptive to our hero’s script. I even found myself thinking: Gee, I really like Cabaret, but it would’ve been better with this number in it.

And from that point, Indecent kept growing on me. The play builds momentum wonderfully. As the scenes progress—including scenes that re-enact actual scenes from God of Vengeance—they shift emotional gears at just the right times, from humor to tension to moments of gentle grace.

Further, there’s never only one thing going on. Indecent spins together layers of narrative and intertwining themes. For example: When God of Vengeance is translated to English, the producer changes the script. He wants the lesbian romance toned down and certain aspects of it twisted around, to make the play mainstream-acceptable and also make Jews look not so bad. The actors protest. In pursuit of a golden egg, he’s squashing the gay goose and mangling the Jewish one. But the show must go on, so the actors dive into the new version … and it’s a struggle (the rehearsals are comical), but they pull it off with gusto … but then it gets shut down anyway.

Stage manager Lemml is furious with playwright Asch for allowing the whole mess to happen—he let someone corrupt his beloved play about the corruption of love!—and by the way, the women who play the daughter and prostitute are falling in love IRL.

Rifkele and Manke (Emily Daly, L, and Meg Pryor) baptize their love in a spring shower.

I don’t know if all of the above really transpired exactly as Indecent shows it, and I don’t care. It works. The intertwining themes include artistic integrity versus financial gain, love versus intolerance, ethnic pride and prejudice versus the desire to be accepted, and probably more. In the closing scenes—which follow up the saga through World War II and the Holocaust—the stakes grow much higher than a busted play.

By the end, there’s hardly an emotion that Indecent leaves untouched. It’s about as complete a journey through the human comedy-slash-catastrophe as one could ask for. Now let me close this review with a caveat and a suggestion.

Don’t Sweat It, Just Get It

Indecent is written to have elements that can be confusing. Informational notes and subtitles are frequently flashed on a screen at the rear of the stage. They’re meant to clarify the story, but they pull you away from the action in order to read them. And—hold your breath—all actors except for Ginsberg, as Lemml, play multiple roles, with an emphasis on “multiple.” In addition to being Asch’s wife, Emily Daly is seven (or is it eight?) other characters. At times you may wonder Who dat?

Suggestion: Don’t sweat every detail. Do what smart viewers do when they’re not catching various meanings and allusions in Shakespeare. Simply let them roll by, and trust the play to cast its spell. You will get what’s to be gotten.

Indecent is a very rich play. The Public’s fine production brings out the richness. Attendance is recommended.

Closing Credits and Ticket Info

Paula Vogel’s Indecent has a score and original music by Lisa Gutkin and Aaron Halva. It is directed for Pittsburgh Public Theater by Risa Brainin, with music direction by John McDaniel. The performers, in alphabetic order: Janice Coppola, Emily Daly, Maury Ginsberg, Laurie Klatscher, Meg Pryor, Robert Tendy, Ricardo Vila-Roger, Erikka Walsh, Spiff Wiegand, and Robert Zukerman.

Through May 19 at the O’Reilly Theater, 621 Penn Ave., Cultural District. For showtimes and tickets, visit The Public on the web or call 412-316-1600.

Choreography for Indecent is by Mariel Greenlee. Scenic design is by Narelle Sissons, costumes by Devon Painter, lighting by Michael Klaers, sound and projection design by Zach Moore. Production stage manager—the real one, not Lemml—is Pamela Brusoski, assisted by Phill Madore.

Photos: Michael Henninger.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer, covers theater for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Follow Entertainment Central

Sign up for the EC Newsletter

Latest Stories