Big Show, Worth a Long Look: ‘Femme Touch’ at The Warhol

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

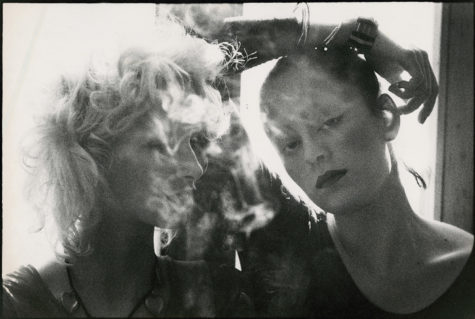

Return with us now to the smoky days of femininity past. Jane Forth (R) and Donna Jordan (behind the cloud) were actors and muses in the films and other doings of Andy Warhol and his circle. They’re among the many figures featured in ‘Femme Touch.’ (photo: ca. 1970, Peter Beard, © 2019)

An intriguing art show has been flying largely under the radar at Pittsburgh’s Andy Warhol Museum. Femme Touch (through January 3) flies largely, period, as it is a sprawling exhibition, with sub-exhibits throughout the galleries of the 7-floor museum. Start anywhere and you are likely to find something that pulls you in.

The show is about women and trans women who were in Andy Warhol’s life—as subjects of his art, as friends or colleagues, or otherwise. There’s quite an assortment of them, and part of the show’s appeal is that winding your way through it can re-create the sensations of wandering through an immense house party to see what’s up: “Oh, look who’s here.” “What’s going on over there?” “Who’s that?”

Themes and moods oscillate as you move along. Jane Forth, one of the most otherworldly looking persons to have lived, casts her spell in a series of entrancing photographs. Julia Warhola—Andy’s mother, a good amateur artist herself, and a connoisseur of kittycats—is represented by her fanciful cat drawings, which capture the essence of cat-ness or least what one might imagine that essence to be. Valerie Solanas, who shot and nearly killed Warhol after he wouldn’t produce a play she had written, gets an elaborate sub-exhibit of her own. It’s in the gallery that displays Warhol’s huge “Skull” and “Gun” paintings.

The show also offers great variety in the kinds of stuff exhibited: art on the walls, films, historic and obscure artifacts. The Solanas exhibit includes a 1967 typescript copy of her SCUM Manifesto, the lengthy document arguing that men have ruined the world and the ultimate solution is to eliminate them, creating utopian female societies. Solanas noted, probably correctly, that scientifically aided reproduction could sustain such a world.

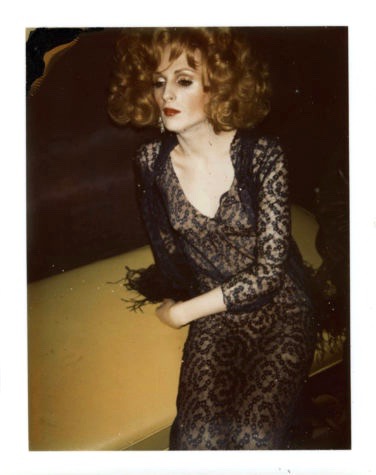

Elsewhere in Femme Touch, other documents tell traces of personal stories. From a dance school on Long Island there’s a 1960 “Certificate of Achievement” in the cha-cha, made out to a youth named Jimmy Slattery. The awardee later achieved fame as the trans film actor Candy Darling, superstarring in Warhol-produced movies and winning an ardent fan base until she died, tragically, of lymphoma at age 29.

The Faces of Women

Every woman has many faces. ‘Red Jackie,’ one of Warhol’s many portraits of the former First Lady, demonstrates that colors and shading may determine which face you’ll see. (image © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

And speaking of reproduction, Warhol may have fathered no children but it was a signature element of his art. His silkscreen-and-acrylic portraits, made with layers and daubs of color applied to blown-up photo images, are striking examples, and the second-floor gallery has a fine selection of them.

One pair of portraits illustrates the power of the technique. Both are made from the same original full-face image. The subject is the performer Grace Jones, a woman with a formidable presence. She is capable of projecting a superhuman aura—somewhere between Nike the goddess of victory and Zombie Apocalypse—and one portrait uses colors and shading to crank this aura to an extreme level. Amazing Grace is coming at you out of a background of electric green, while the features of her visage that would normally appear darkest are reversed, startlingly, into white. Her deep-set eyes are masked by ghostly white eyeshadow. Her tight fade hairdo frames her head in a bristling white corona …

And meanwhile, hanging nearby is a different Grace. This portrait is done in warm earth tones mixed with reds, with more natural shadings. It brings her back to Earth. The warmth of the colors allows her to radiate, which she does, intensely, but it’s a radiation you can relate to—because here, she is more like someone you’d know: just the Jones girl next door.

Motion Pictures

Something to keep in mind when watching any Warhol film: Don’t wait for the car chase. There won’t be one. But ‘Nico/Nico Crying’ is a marvelous exercise in contemplative watching. (film still © The Andy Warhol Museum)

The films and videos in Femme Touch are a mixed bag, in terms of both subject matter and aesthetic interest. One I would recommend highly is Nico/Nico Crying. The Velvet Underground vocalist doesn’t sing in it, nor does she move around much, or even cry much. Yet it is hard to take your eyes off Nico not doing anything. You’re kept riveted by the lighting effects, which throw a constantly shifting array of patterns, shapes, and colors across Nico’s face. Cheap tricks from the Sixties light-show playbook, maybe, but I found myself profoundly moved at times as I watched.

Although Nico isn’t in a state of “doing,” she is at every moment in a state of being, thinking, and feeling, as any human would be. And for me, the incessant dancing of patterns and colors on her face seemed to help to bring to the surface the incessant dance that goes on inside each of us.

Nico/Nico Crying is 66 minutes long, playing on a continuous loop. You needn’t sit through the whole thing—I’ve watched various segments during repeated trips to The Warhol—and what you see will depend on when you tune in. The same is true for many films in Femme Touch. In a part of the show featuring the jazz singer Tally Brown, you can view what appears to be a film montage of her attempting a guest performance at Warhol’s Factory. It’s done more in the style of a clowning-around home video than a concert film, and some of it comes across as sophomoric satire. (For example, Brown laughing as she sings “God Bless America,” while distracted by pranksters who festoon the set with toilet paper and such.)

But one early bit is awesome. Brown, decked in a gown and standing somewhat nervously at the mic, announces that it’s her first time in a Warhol film. The camera goes tight as she’s about to sing. And instead she just lets out a long, majestic howl. Now, that is scat.

A lot of the Warhol film oeuvre is best viewed as if you’re at a jazz club where the musicians are improvising. The typical approach was to put witty and/or talented persons in front of the camera and let them jam. You may get some boring riffs or some awkward false starts, but also mesmerizing passages that stay with you.

Oh, really, Susan? International Velvet, a.k.a. Susan Bottomly, brings a high coiffure and ham-handed acting to the party in Warhol’s short film ‘Paraphernalia.’ (still frame © The Andy Warhol Museum)

‘He Lived in a Feminine World’

Femme Touch grew from more than two years of brainstorming and planning by The Warhol’s curatorial staff, Chief Curator José Carlos Diaz said in a phone interview. The goal was to put together a show that “would make the museum more female-focused,” he said—which, on the face of it, looked easy, because “Andy Warhol lived very much in a feminine world.” In his early work as a commercial artist, he illustrated women’s fashion ads. He shared an apartment with his mother. He idolized female celebrities, painted their portraits, had close female friends, and so forth.

However, “it would’ve been a little too easy” just to choose Warhol’s own depictions of femininity, like “his paintings of Marilyn and Jackie and Liz,” Diaz said. “We wanted to flip who gets seen in a museum dedicated to a white male artist. We wanted to present a Warhol narrative without Warhol being on center stage.”

Gradually, a concept emerged. The show would use items like films and personal memorabilia to let the subjects speak for themselves as much as possible. It would include many of the trans women and drag queens in Warhol’s circle, i.e., persons whose assigned sex was male who identified or presented as femme. And, along with some high-profile figures, the show would feature “individuals whose stories are not so well known,” Diaz said.

Candy Darling acted in plays including the premiere of Tennessee Williams’ ‘Small Craft Warning.’ Along with others in Warhol’s circle, notably Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn, she helped to break new ground for trans performers on stage and screen. (photo: Andy Warhol, 1969, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

The results are evident throughout. In the second-floor gallery, around the corner from paired portraits of Debbie Harry and Dolly Parton, is an entire wall displaying spectacular studies of the little-known RuPaul forerunner Wilhelmina Ross. Another gallery screens the seldom-seen 1973 feature film L’Amour, co-made by Warhol and Paul Morrissey and starring Donna Jordan and Jane Forth. The late queen Mario Montez comes to life in a memorable short film, wherein Montez and a pal co-consume a hamburger, hands-free.

Femme Touch even pays tribute to a long-forgotten bomb. Whereas there were femmes who branched beyond the Warhol scene into live theater, with some measure of success (Jackie Curtis wrote and acted in plays; Candy Darling acted), Andy’s own venture into playwriting didn’t travel as well. One gallery has mementos from Warhol’s 1971 play Pork. He based the script, in part, on conversations with his good friend and associate Brigid Berlin, who apparently had a fertile imagination. Characters included Amanda Pork, Vulva, Miss Hell, and 1st Pepsodent Twin. Pork played in London, where the Daily Mirror—in a review you can read, along with the play’s script—called it “Top of the Flops.”

And yet a close reading of Pork might reveal pearls of wisdom amid the swine. At the risk of giving spoilers, here is a Zen-like exchange: “We missed everything good.” “Well, what’s left?” “Everything else.”

Don’t miss a good exhibition. Catch Femme Touch while you can.

Visitor Info and Closing Credits

Femme Touch continues through January 3 at 117 Sandusky St., North Side. To maintain limits on numbers of guests in the building, advance online reservation for entry at a particular time is required, and of course you’ll want to bring a mask or face covering when you come. The Andy Warhol Museum is open 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. most days and until 10 p.m. Fridays, but is closed on Tuesdays and major holidays. Mondays from 10 a.m. – noon is a time reserved for seniors and others with Covid-19 risk factors.

For more information about Femme Touch and seeing the show, visit The Warhol on the web or call 412-237-8300. Femme Touch is organized by José Carlos Diaz, the museum’s chief curator, along with a team of its curators and educators: Nicole Dezelon, Ben Harrison, Geralyn Huxley, Danielle Linzer, and Greg Pierce.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer, covers visual arts and theater for Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Follow Entertainment Central

Sign up for the EC Newsletter

Latest Stories