‘Unseen’ Art at The Warhol: More Than We Knew

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Edie Sedgwick became a close friend of Andy Warhol, acted in his films, and was a rising star in the New York fashion scene—all before tragically dying young. A short film-to-video clip of Edie is part of the ‘Unseen’ exhibition at The Warhol. This still frame shows Edie in her prime, glowing through a rose-colored haze. (Image © The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved.)

There is nothing like The Andy Warhol Museum, because there has been nobody like Andy Warhol. Who else created thousands of artworks on themes and subjects ranging from oral sex to spirituality, and from Campbell’s Soup to Kafka? What other artist also made films and produced feature-length movies, managed an influential rock band (the Velvet Underground), co-founded a magazine (Interview), survived an assassination attempt that left him riddled with bullet wounds, hosted TV shows, was openly gay but a closeted Catholic, wore wigs in styles from natural to surreal, has a livestreamed gravesite, and, when asked if he ate fast food, said “No, I eat food fast”?

The Warhol Museum is singular in its own right. Housed in a seven-story former warehouse, this is the largest U.S. museum focused on a single artist. It’s hard to fathom how prolific Andy was: Along with his hard-working nature, he used assistants and worked in rapid methods such as screen printing, to make multiple variations of a single image. Although he sold lots of pieces, plenty remained available after his death in 1987, and so did multitudes of his films and still photos, boxes full of objects he’d collected, et cetera. Altogether, the museum holds vastly more stuff than can be displayed at once.

Of course sheer quantity isn’t the attraction. Rather, visitors tend to be fascinated by the wide-ranging scope of Andy’s artistic inquiries—touring The Warhol is almost like touring a museum of Western culture, through his eyes—and by the striking ways in which he conveyed his visions. Many artworks look glaringly simple, but have shapes and shades of subtle intensity (or, if you prefer, intense subtlety) that invite you to see anew. And if you need a pretext for visiting, one exists right now. A special exhibition titled Unseen runs through March 4. It showcases over 60 works that are well worth contemplating but hadn’t ever been put on view.

Sex, Death, and Secrets of the Self

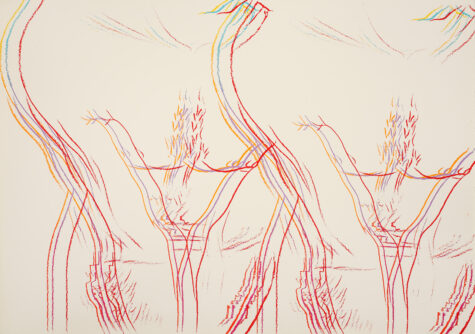

Some pieces in the Unseen show are sexually explicit. Sorry, authorized photos of these were not offered to the media. Here is the sexiest picture we’re able to share:

Andy Warhol’s ‘Torso (Double)’ emanates strong, suggestive vibrations. Image © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

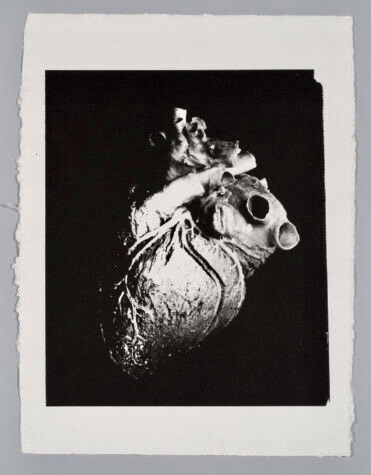

Other pictures are spooky. You know that you have a heart pumping inside your breast, yet it can be disquieting to see the pump unplugged, disembodied, and rendered in a shadowy screen print:

The screen print titled simply ‘Heart’ was made around 1979. Image © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

To amplify the effect, Unseen displays a pair of “Heart” prints sandwiched around a print of an object that normally would seem cheerful: a chocolate Easter bunny wrapped in foil. The bunny, however, is done in the same spectral black-and-white tones. Seen that way, the crinkles in the foil glisten darkly, like serpentine scales, and the candy animal becomes the hideous Rabbit of Death—flanked, as if in a ritual sacrifice, by once-throbbing but now-silent hearts. Sneer if you want at my melodramatic attempt to describe the viewing experience. I have not seen a more chilling triptych than the dead hearts and bad bunny.

Elsewhere are versions of full-color prints that Warhol made for his 1975 show Ladies and Gentlemen. The show was dramatic: a series of portraits of transgender women who’d been scratching out a living as street people in New York. For whatever reasons, Andy didn’t include the pictures now displayed in Unseen. And a couple look quite different from his usual style of portraiture.

Typically, Warhol made a portrait by starting from a photograph of the subject—either a photo he’d taken, or an existing photo (as with his famous Marilyn Monroe portraits). Then he’d have the image enlarged and screen-print it, to overlay various areas of color and shading; hand-painted areas came in as well. This process altered the source photo—in some cases subtly, in others sensationally—resulting in a portrait that highlighted certain features of the person and created a distinctive mood. But here’s the difference. In nearly all of the portraits, you can see the contours of an original photo punching through. Not so with “Ladies and Gentlemen (Alphanso Panell),” below.

Warhol’s ‘Ladies and Gentlemen (Alphanso Panell).’ Image © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

This portrait of a trans woman is itself a trans-portrait. It migrates into symbolic abstraction. Alphanso appears to wear a mask. (To which one could say, don’t we all?) Alphanso, like many of us, lives under a hood from where she ventures to speak and look. And the pinkish blaze at the bottom is the flesh that she wants the world to see. All of which sums up my interpretation and emotional reaction. The artist might have had something else in mind.

The Director’s Cut

The full title of the exhibit is Unseen: Permanent Collection Works. It was conceived by the director of The Andy Warhol Museum, Patrick Moore, who went on to curate the show.

In a phone interview, he recalled how the idea came: “I’d seen things hanging in the museum, or in some of the traveling exhibitions that we do, that I had never seen before. And I’ve been here for 13 years,” Moore said. “So eventually I thought, How many objects are there that I don’t know about, and maybe nobody knows about?” He asked The Warhol staff to generate a list of artworks that hadn’t been displayed or sent out on loan. “A couple of hundred” leaped out, and from those, Moore chose the pieces for Unseen.

His selection criteria? “Part of it was personal, [choosing] pieces that spoke to me. Part of it was which ones I thought were most visually compelling, and would look great together.” Also, “sexual works that hadn’t been shown” made up a special category: “I felt we had a responsibility to show that work because Warhol was an openly gay man. I felt it was important that we didn’t, either intentionally or unintentionally, somehow erase his sexuality.”

Moore said he hoped visitors to Unseen would experience a sense of discovery—and in some cases, the show helped him and his staff discover things they hadn’t known. One strange picture is printed, curiously, on a silk scarf. It shows a Christlike figure seated in meditation. He’s superimposed on a pyramid crowned by a searching eye, similar to the pyramid on the back of a dollar bill, while bold lettering across the top says THE ONLY WAY OUT … IS IN! It’s believed that Warhol borrowed the source image from one of the flyers handed out by people proselytizing for causes and beliefs on the streets and subways of New York.

But there’s more to the story. “Now that we’ve shown it, people have said ‘Oh yeah, I know about that piece,’” said Moore. It seems Warhol put the picture on multiple scarves, which he gave as Christmas gifts to friends including the artist Keith Haring.

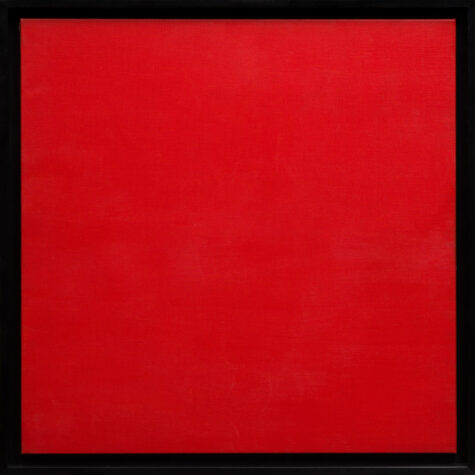

A visual pun on Moscow’s Red Square? Unlikely. Warhol’s ‘Red Blank’ has an enigmatic backstory. (Image © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

Other pieces in Unseen remain mysterious. The large canvas “Red ‘Blank’” is just a big red square. Moore explained that when Warhol did a series of related paintings, he would sometimes include a “Blank” painted simply in a solid color. The red one was bundled with a group of Liz Taylor portraits he sent on consignment to the Los Angeles art dealer Irving Blum, who sold the Liz pictures but eventually donated “Red ‘Blank’” to the museum. Moore said he had asked Blum “What’s the deal with this painting? Why did you give it to us?” He said Blum replied “Because I didn’t know what to do with it.” The dealer felt he couldn’t sell it, “because Andy would never explain what it was” or what it was for.

Moore noted that people have speculated on the intention of the Blank paintings: “Was Warhol saying that his shocking car-crash images or movie-star images had been drained of their meaning, and all that was left was a blank? That might be true. But other people have said, No, he just wanted to make the overall package bigger so he could charge more. And that sort of has the ring of truth to it.”

The Whole Body of Work: A Love Letter?

Artists’ intentions can be elusive and, in a sense, irrelevant. Once the art is out there, it is what it is and it’s up to you what to make of it.

The rest of the Warhol Museum offers plenty of material for meaning-making (or for sheer sensory enjoyment, if that’s what you seek). Displays change frequently as pieces from the permanent collection are rotated in and out. When I mentioned to Patrick Moore that visiting The Warhol struck me as a journey through 20th-century Western culture, Moore added a coda of his own.

“I think the decades that were the height of Warhol’s career—the ‘60s and ‘70s, even the ‘80s—represented a time when we were experimental and hopeful. And when American culture ruled the globe. So, in a way, you can look at Warhol’s life and work as a bit of a love letter to America. Not an uncomplicated one, but a letter from a time when maybe we were at our best.”

Upstairs from the Unseen show, stop to spend some time amid the ‘Silver Clouds.’ Their company is mesmerizing. Perhaps uplifting. Photo © Abby Warhola.

Closing Credits and Visitor Info

Unseen: Permanent Collection Works is curated by The Warhol’s Patrick Moore with support from Matt Gray, director of archives; independent researcher Signe Watson, and the collections and exhibition department of The Warhol.

Through March 4 at 117 Sandusky St., North Side. The Andy Warhol Museum is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. most days, until 10 p.m. in the evening on Fridays, and closed Tuesdays. See the Unseen web page to learn more about the show.

Mike Vargo, a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer, contributes reviews of the visual arts and theater to Entertainment Central.

Share on Social Media

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Follow Entertainment Central

Sign up for the EC Newsletter

Latest Stories